Danse Macabre - Interview with Chris Pickett and Wythe Marschall of Stillfleet Studio

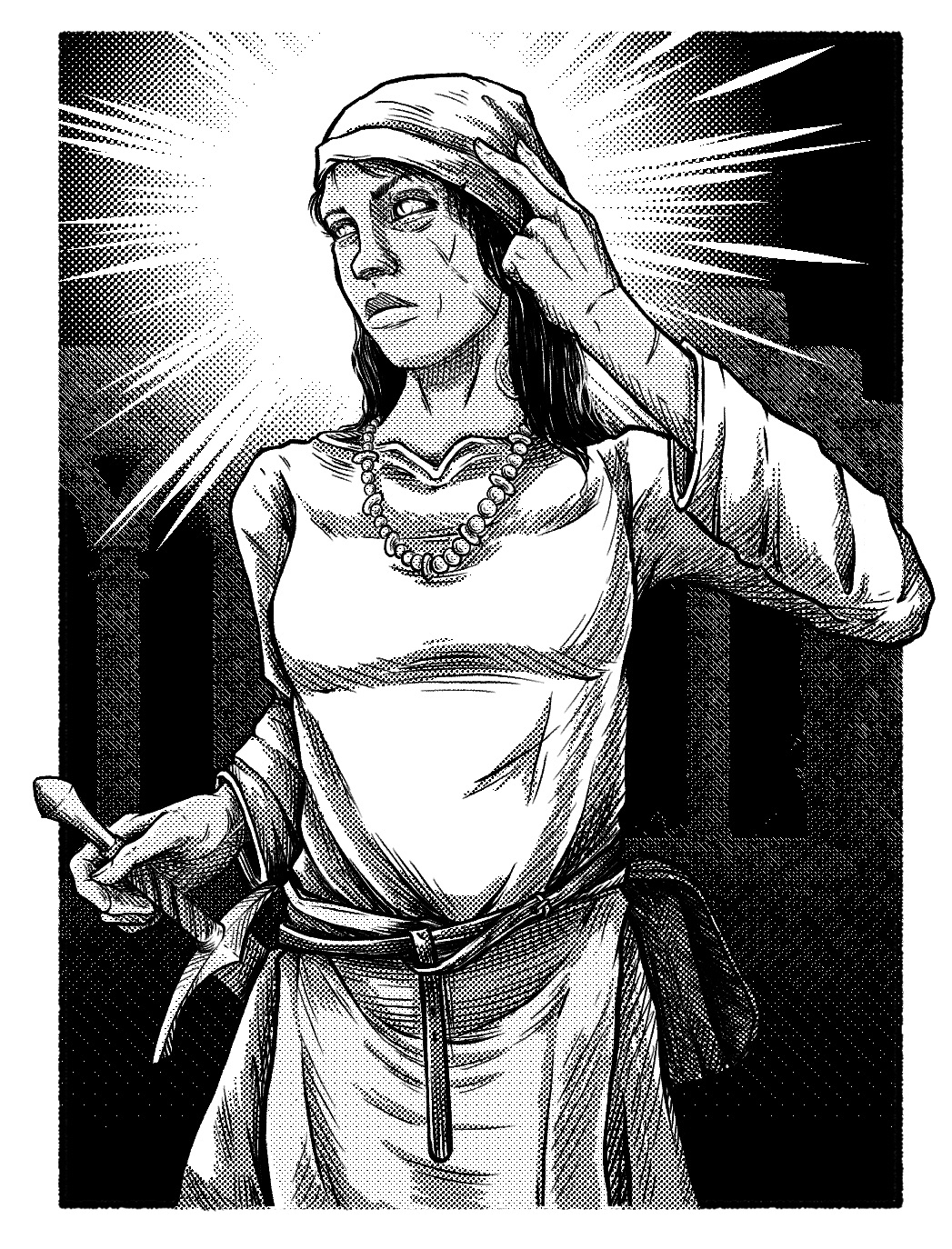

We go deep on historical fantasy, mutations, and the Grit System with the team behind Danse Macabre.

Our good friends over at Stillfleet Studio just launched a Kickstarter for their historical-fantasy RPG Danse Macabre, so I set aside some time to chat with the game's designer and the studio lead, Borough Bound has done a bunch of crossover work with Stillfleet—and we may do more depending on how some stretch goals turn out—and I just generally love everything the studio puts out. Please give the Kickstarter a look and browse all of the other fabulous RPG products Stillfleet Studio has released.

P.S. If you enjoy this conversation, listen to Wythe and Chris interview me and our art director James on their podcast Why We Roll.

Will Savino: Normally when I start an interview, the first question is something vague and philosophical about your approach to making art and thinking about RPGs… but you have a thing that is cool that we have to talk about.

So, Chris, why don’t you give us the elevator pitch for Danse Macabre so people know what the hell we’re talking about?

Chris Pickett: Sure, yeah, hey, what’s up? I’m Christopher Pickett. I'm the creator of Danse Macabre, and I’m also a multimedia artist living in Brooklyn, New York. Danse Macabre is a medieval horror roleplaying game. It’s set in real world history in 1390, but the big flip that we've put on it is that death has stopped working the way that it's supposed to. So, now, whenever characters die—whether NPC or player characters—they are revived within a few hours. Every time they are brought back to life from false death, they come back with these body horror mutations that we call maleficia.

So that's the core novum. The core rule book is set in Constantinople, so it concerns the city and region around it, as well as setting people up with how to play the game, how to be a messed-up little mutant guy in 1390.

Will Savino: We also have Wythe Marschall here. Wythe, you run the studio that is publishing Danse Macabre.

Wythe Marschall: Yes. Stillfleet Studio is publishing Danse Macabre. I would also say the Studio is co-developing it. My role on the project, in addition to project managing, is lead structural editor. We have a great copy editor (Jedd Cole) and a historical consulting editor (Dr. Erica Bridges), and they're also doing close reads of the core Danse Macabre Rulebook.

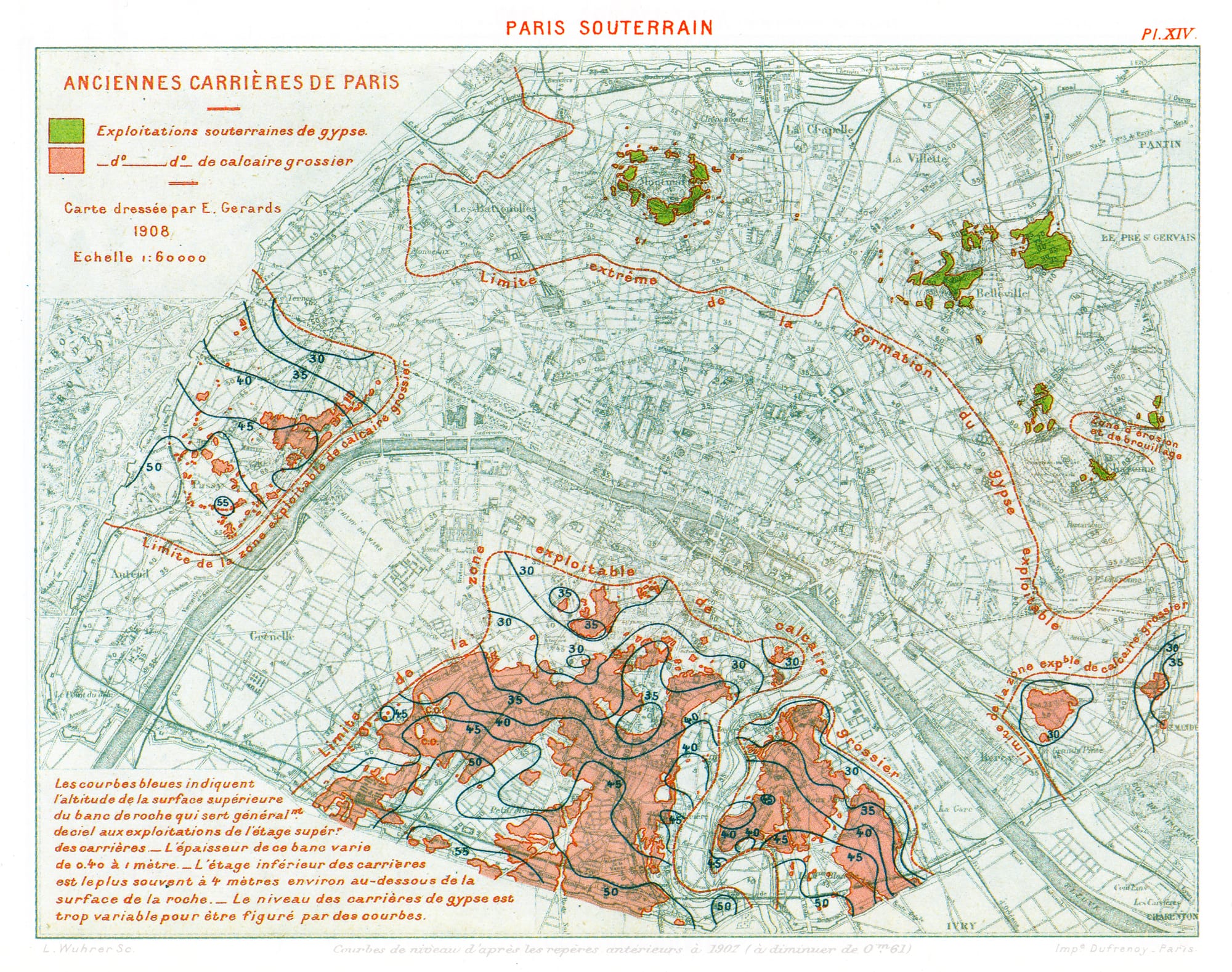

I'm structurally editing everything and then also writing another book. We have the Danse Macabre Rulebook, that's all Chris’s writing; a book called Guide to the Abandoned World, that's a bunch of different settings by a bunch of different authors including a chapter by me, a chapter by Chris, and a bunch of guests; and then Unsunken: Paris Below, which is our mega-dungeon/campaign-setting book, which I'm writing. It’s another alt setting, where it's the same rules… just different factions and somewhat different play loops. We're trying to allow for Danse Macabre to be used for OSR dungeon crawls specifically but still have this very historical idea that you're in Paris, which is actually on top of gypsum mines, limestone quarries, and Roman sewers.

Will Savino: Is that true? Is Paris built on gypsum mines?

Chris Pickett. Yeah, that's a historical fact. It's what eventually became the catacombs in the mid-1700s. That’s when they converted them into what we now know as the catacombs. All the way back to the Roman occupation of Gaul, they were digging underneath what is now Paris.

Wythe Marschall: Even before the Romans. The Romans did a lot, but actually the Gauls had mines. There might have been people there before the Parisii—the tribe after which Paris is named—so it's a great built-in setting just from reality. When googling it, I was like, “Oh wow, well, this is definitely gonna be a spooky place,” right?

Chris Pickett: Yeah, kind of a gimme in a lot of ways.

Will Savino: Okay, this is obvious… I am not a PhD in medieval European history.

Wythe Marschall: Whaaaat?

Will Savino: [laughs] But, I believe it's still appropriate for me to play this game.

Wythe Marschall: Yes.

Will Savino: How do you balance that? Also, I don't know what the fuck people need gypsum for. Why were they even mining that? What is gypsum for? What do you use gypsum for?

Wythe Marschall: I know a lot more about the limestone.

Will Savino: I don't care about limestone! I know about limestone. You cap the pyramids with it.

Chris Pickett: We need to know about gypsum now!

Will Savino: Don't look it up.

Wythe Marschall: [looks it up]

Sculpture, construction, art, medicine, plaster… Oh, plaster! Plaster of Paris, right? Sorry. I know the answer.

Will Savino: Is that why they call it that?

Wythe Marschall: That is why they call it plaster of Paris.

So in our game, Paris is still the biggest city in Western Europe despite the apocalypse. Or, actually, in Chris's game, a lot of cities get bigger as people run away from folk-horror, zombie-haunted farmlands, right? They go to the big city for protection from the local warlord. So Paris is just like the biggest, warlord-iest, Mad Max-iest medieval setting.

Will Savino: Let’s talk about the medieval history aspect of it, because I have to admit: I would be a little bit intimidated to GM a historical fiction game unless it's about like… 20th-century Buffalo, New York, because I don’t feel like an expert…

Wythe Marschall: Coming soon from Stillfleet Studio…

Chris Pickett: Danse Macabre: Buffalo.

Will Savino: Absolutely, don't fucking joke. I would make that game.

Anyway, everything in your marketing materials suggests that you don't need to be a history buff. You don't need to be an expert. You can play this game without knowing a lick of medieval European history. How do you square that circle?

Chris Pickett: Yeah, it's funny. We were talking about this earlier today. I just wrapped up writing the big lore chapter about Constantinople, and it is definitely a juggling act. You want to have enough of the actual medieval history to give people a sense of the feel of the time and a sense of the overall vibe. Ultimately, at least for me, the game is about embodying your character and questioning what it means to be human in weird times and all of that good stuff. So I feel like that experience had to come first.

There are a lot of historically specific things, like a lot of the weaponry names and things like that,

as well as armor… just things that players and GMs both can touch are very specific.

But at the same time, we don't spend an inordinate amount of time going into the whole history of the region, the whole history of the world, just because it's too much! As a game, it's got to be fun first.

So really, structurally, it is built out like an OSR game. There are optional rules for wilderness crawls. There are rules for some dungeon crawl stuff. It's very fighty. There are lots of monsters, which are called demoniacs. They’re people who have been transformed into basically zombies—for lack of a better term—by just dying too many times and losing a piece of themself every time they die.

It’s difficult. I always want to go really long on the history stuff. Early iterations of some chapters definitely had that. It’s kind of about, for me, just word-vomiting, getting all of that information out onto the page and then taking a step back and being like, “Okay, is this useful information for the player? Does this establish the kind of overall vibe that we're going for? Or is this actually a distraction?

And then, from there, just trying to put the player experience first while still giving those details and trying to give a look at what it was like to live at that time.

Will Savino: I also don't think that this is a unique friction for a historical fantasy game, because, y’know, if you’re writing anything about the Forgotten Realms or Eberron or any other fantasy setting, like… at a certain point, you have to tell yourself, “Okay, the GMs and the players don't need to read 100 pages about all of the different wars between dark-elf factions or whatever, right?” No matter what, there’s always a limit to what is useful for enhancing verisimilitude, what is going to be good for gameplay, and what legitimately is useful flavor to get people in the right headspace.

And that’s true of historical fiction. You can just write the stuff that is helpful. If people come in being, like, “Well, I do know a couple things about medieval Ottomans,” they can include that too, or they can make it up! Because what do you lose by making it up?

Chris Pickett: Yeah, I mean I don’t think that you lose anything. And to your point, I think that that was an early “aha moment” for me. It was realizing that we have established settings in D&D, or even like the general Western fantasy canon, right? There are all these tropes and established fictions that we already play around in. Even running a game of Dungeons & Dragons or any kind of dungeon-crawl game… That stuff fades into the background most of the time. The reams and reams, the books’ worth of lore that are out there—it’s there for you to consult and to get ideas from, and that’s great.

But, to your point, nobody expects GMs to fully research the Forgotten Realms and know about all the geopolitics of the Forgotten Realms.

So we can kind of pick and choose. Throughout the book, we have callouts, so if there’s a historically specific term—something that could cause friction for a player—we go through and briefly explain those things without getting too deep into the weeds about it. We're trying to toe the line to have a little bit of both.

Wythe Marschall: You can go on Wikipedia and find a whole web of articles about medieval mining and skim them in five minutes. And as a GM, most of it is not gonna come up, but you might have a couple ideas. It’ll help you set yourself in the mood of “this isn’t fantasy,” other than this zombie-apocalypse novum, that one difference.

But the rest of the world, Chris has treated—and we now have treated as a team—as very much like… no, it’s cool that it’s actually real, and there’s a lot of real stuff.

The other sort of interesting novum is a social one, which is that we’re treating people very symmetrically and veiling prejudices that were very real in the Middle Ages. They were very different than they are today, but we’re just saying, “Look guys, it’s been 30 years of a literal apocalypse. Death is not working right.” So people have set aside a lot of that. I think between those two things, it actually feels very approachable as a GM to come up with ideas, because like there’s a ton of ideas in your head.

You can leave out anything that seems confusing or is just like, “Okay, I’m not gonna deal with some sort of real-life racism between two groups of people who no longer exist a thousand years ago.”

You can actually tell really fun D&D-like OSR-like stories in the real world, and the real world edge gets players who know very little involved, because they know that Constantinople is a place, or Paris is a place, or yeah, Japan is a place, right? You can get them to lean in and say, “I’m there with you. There’s no magic. I’m a real person. I don’t want to get eaten by zombies.”

It's not that hard. It turns into The Walking Dead in a nice way—in a fun way—very quickly.

Will Savino: We have preconceptions about fantasy, so much of which stems from Tolkien and generations of D&D and so forth, but also that can cause frictions in standard-ish fantasy games because people have these notions of the fantasies that they want to live out. “Oh, I want to be the elven ranger” or whatever.

Chris Pickett: It’s always the elven ranger.

Will Savino: And then maybe that doesn’t actually match the story that the GM wants to tell or the nuanced lore of their homebrew world.

It’s almost an advantage in historical fantasy to say that—if there’s a discrepancy about something—it’s not even necessarily going to be decided by GM fiat. We’ll just go on Wikipedia and say, “What is the nearest town 25 miles northwest of Constantinople?” or whatever.

But also, even though there’s a lot of crazy stuff in Danse Macabre—which we will absolutely get to—there’s a level of approachability because probably people know a little bit more about medieval history than they think. Well, probably people are wrong about a whole bunch of stuff about medieval history, but at least they know the shape of the Mediterranean Sea, right? They know where population centers might be, and that is at least something of a jumping-off point.

Chris Pickett: Yeah, I think so. We did a big four-session-long, two-table playtest at the Twenty Sided Store here in Brooklyn, which was a lot of fun. Wythe and I were co-GMing at the same time, and we were running two different groups that were on the same overarching plot, but going to separate places, finding out different things, and then coming back together at the end.

I think the thing those sessions made me realize is that a lot of our players already have, if not the specifics, they at least have the outlines of the history. They at least have the outline of the vibe that you’re going for with the game. I think that using that as a jumping-off point is actually really successful and easy for a lot of people. I do think that looking at it from a distance, it seems a little bit intimidating, but for one thing, the Grit System—which Wythe came up with—is easy to learn, it’s easy to get into. You’re not really worried about mechanics; you can just jump into the Medievalism of the game as well as the horror elements of the game.

Will Savino: Well, let’s talk about the horror and the fantasy aspects, because they’re cool. I think some of your copy at some point said something like, “a fantasy campaign without magic,” and like… the player characters don’t have spells, but this is a pretty magical world, right? Can you go over the real basics of what is magical about the world of Danse Macabre?

Chris Pickett: The main thing that is magical about it is just that you die and you revive over and over. Nobody can die naturally for the most part. Well, I guess this is magical as well: there is a way to die naturally which is by collecting “relics,” which is kind of our catch-all term for artifacts and things that are made before the “Abandonment of Death,” which is the big overarching event that the player characters find themselves in, basically the moment that death stops working. It’s like, “Oh, we've been abandoned.”

You have these relics that, when people sing to them, they light up, and they glow with this mysterious energy called “quintessence,” and if you die while you’re being bathed in this light, you die normally. So yeah, quintessence is very magical in a way.

And then, also, just dying and reviving with these body horror mutations. We don’t explain the Abandonment; we don’t explain where it comes from, why it happened. It just is, which is a thing that I was very insistent on, just because I personally think that's more interesting and gives GMs room to wiggle around and figure out what they want it to be.

The body horror, the quintessence… those are definitely magical elements that just go unexplained. My bugbear with TTRPGs and the use of magic systems is just that, if you’re able to reshape reality with a word or with thoughts, you’re going to be a crazy person who is way too powerful. I wanted to avoid having spells and these ways of altering reality and things like that partially because I wanted to instill a lack of control. I don’t want to say a “lack of agency,” but definitely a lack of control for the player characters.

The mutations that you get, the “maleficia,” are totally random every time you die. You roll a d100. We have a list of 100 different mutations with three different levels, so effectively 300 mutations that you can get.

Will Savino: Well, this is why Wythe agreed to publish the book, obviously.

Wythe Marschall: [laughs] Love a list!

Chris Pickett: Just a big, massive deluge of powers. But yeah, big ups to our editor, Jedd Cole, for going through all of that.

Will Savino: But having magical abilities, that would make sense in a game about figuring out that it was a dark god who caused the Abandonment and then going on a quest to slay that dark god. But the vibe with Danse Macabre is meant to be much more picaresque and human, and it’s more about about, “Here's what life is like for people who do still have to brave these horrors and put themselves in harm’s way.” But they’re not going to discover the cause, and they’re not going to undo the cause, and they’re not going to remake the world. But, they can hopefully make life a little better for themselves and their family and loved ones.

Wythe Marschall: Yeah, you can play it that way. With any of these games, there’s an assumed way to play, and I think our way to play Danse Macabre is actually not that picaresque, and it’s definitely also not the big epic thing. It’s almost more like a social noir. It’s been 30 years, the world is very different, but life goes on, and there are now different sorts of factions. If you’re being sent out on adventures, Chris was thinking, “Who would be doing adventuring, and what would that look like?”

Well, you’re getting relics from before the Abandonment so that we can sing at them and release quintessence and people can die normally. Basically the church choir becomes the secret intelligence agency for any given faction, and they’re sending you out to get relics and also sometimes slay demoniacs who were threatening normal people, and also maybe fighting other cities.You know, again, think of The Walking Dead or any zombie fiction. You have these dual pressures of, “Oh no, apocalypse,” but also, “Humans are the real final boss,” right?

It’s actually a game more like Red Markets or any zombie game than it is a true picaresque or epic 5e, “We’re gonna go slay god and save everyone.”

Will Savino: That description also makes it feel so much more synergistic with Stillfleet [the first game from Stillfleet Studio]. There is a common theme of power systems being entrenched, and you, the player, have to live in a world where you’re not gonna overthrow the great authorities. The best you can do is nudge things in one direction or another, but you’re essentially freelancers for, y’know, basically evil governments, factions, capitalist powers, etc.

Whether it’s a hundred billion years in the future, or the apocalypse has already happened and death doesn’t work anymore, no matter what, so long as anyone is still alive, power structures will require freelancers to be hurt.

Chris Pickett: Yeah, absolutely. I do think that the big difference between Danse Macabre and Stillfeet in that regard is that—at least in the core rulebook—you’re not freelancers. You are convicted criminals.

Will Savino: What’s the difference? Literally, what is the difference?

Chris Pickett: [laughs] That’s a good question actually. You don’t have a choice in the matter, right?

Will Savino: I’ve been condemned to freelance life for a long time.

Chris Pickett: Haven’t we all, brother?

Will Savino: [laughs]

Chris Pickett: You’re basically conscripted into service in Danse Macabre. So really drilling down on what you were saying, Will, about like… yes, you’re kind of just a person. There’s this huge apocalypse, an active apocalypse happening around you which you don’t have answers for. You don’t have a way necessarily of touching or changing it. And then you’re also entrenched in these political systems, which are changing over time. We have some factions that are newer, or like newer expressions of previously existing groups or communities.

The Bogomils, for example, were a dualist, gnostic Christian sect originally in the Balkans. They’re one of the factions in Danse Macabre. They’re having a revival, essentially.

Wythe Marschall: You might know them as the Cathars.

Will Savino: When I’m transcribing this, I’m going to need you to spell so many of these words.

Chris Pickett: [laughs] But yeah, they were cool! They were arguably early socialists, their leadership was gender-agnostic, and it was more about how ascetic of a lifestyle you can lead. That was how you got fame in the Bogomil/Cathar community.

Will Savino: So you just made a good faction. You just made good guys. That’s pretty rare.

Chris Pickett: There’s one faction that I really like, and that I champion, and that is the Bogomils, for sure.

But then you also have the Patriarchate of Constantinople, which is the Eastern Orthodox Church. They’re still holding on, they’re still trying to say people should not abandon the faith, and all that good stuff. So yeah, the power structures are constantly shifting.

Will Savino: You have the opportunity to—I don’t want to say “sanitize,” because that undermines what you're doing—but you get the chance to rewrite things so that the game addresses sensitivity concerns. You know, 30 years in the future after the Abandonment, maybe let’s not worry about really basic racism, slavery, etc.

Wythe Marschall: Yeah, exactly.

Will Savino: But, no matter what, you have to address religion, and I’m curious how you balance critiques of organized religion with the fact that demonstrably, singing to relics seems to be divinely potent. So, there is some objective reality to—if not religion—at least divinity. How have you been able to make a game that’s not just like, “Historically, Christianity has been very bad for the world”? Or do you just say that?

Chris Pickett: I don’t outright say that anywhere in the text. In the Rulebook, the main setting of Constantinople, the city has basically been split in a kind of Cold War Berlin situation. So half of Constantinople is still controlled by the Romans, the Byzantines, with all kinds of independent communities. And then the other half of the city is controlled by a faction of Ottomans who basically allied themselves with the current emperor that’s sitting on the throne.

There are these moments where it’s like, we have to acknowledge there’s a tension between the Christian church—churches—and the body of Islamic scholars and lawyers, etc. They’re written as faction rivals, not warring against each other. They have this grudging acceptance of each other while also trying to simultaneously undermine the other and each other faction.

Will Savino: From a game design point-of-view, it seems a lot easier to have two. Literally just saying, well, there’s Christianity, and there’s Islam, and there are other people as well, and there are flaws with everybody. From a gameplay standpoint, it makes it easier to be like, “See, we’re not just saying ‘one group equals bad’ or anything like that.”

Chris Pickett: Yeah, and that goes back to what Wythe was saying about treating different communities and different factions symmetrically, right? We have to acknowledge that people are going to struggle for power or do desperate things while they're struggling for power. It doesn’t mean that they’re necessarily evil. It means that they have a goal and that they’re moving towards that goal.

Wythe Marschall: I also think it’s worth highlighting that it’s a particular viewpoint to view [the Abandonment, maleficia, and quintessence] as somehow divine. The book actually tries really hard to say that there aren’t magic powers. There are just mutations tied to different kinds of bodies, and when death stops working the way it has worked up until now, it’s not clear why. It’s the scythe of shaking faith across every community. So whether you’re very devoutly Christian, Muslim, Jewish, or in some other setting, it doesn’t really matter, because a lot of people just abandon traditional faiths.

I think this happens in a lot of apocalypse fiction. New religions arise, almost like cargo cult-ish kind views. “Yeah, well, I don’t know. My cousin in the other village said that a snake was born with three heads. So that must mean… I’m gonna go worship that guy.” I think what the game does is just try to treat everyone symmetrically. Especially the big ones, right? I mean Christianity, Judaism, Islam. Like, they’re all people trying to live. All of the clerics who are well-meaning, more or less, are just trying to take care of their flock. They don’t really have any answers, and they admit that! Over time, they remain sources of stability. They still are, but kind of for different reasons. People have modernized more rapidly, and now these people—who are custodians of religious institutions—they’re trusted because they’re controlling politics in a way, because they have all these relics. They tend to have the relics already, they have the choirs already, and they have the social trust.

What we try to militate against in every book is, look, just don’t cosplay “clash of civilization” racist bullshit. That’s the least interesting, it’s not really that accurate—other than just like anti-Semitism, which we’re just like, don’t do that. That’s just dumb and bad.

Chris Pickett: Yeah, please don’t do that.

Wythe Marschall: You can have all kinds of other factions like Chris is alluding to. Those are kind of real, like there were different groups of Seljuks, and different groups of Ottomans, and different groups of Romans (i.e., Greek-speaking people who call themselves part of a Roman Empire), who had different alliances at different times. So that’s not something Chris totally made up. I mean, you were drawing on that to build a cool zombie-RPG setting, but that’s a real thing.

Chris Pickett: Similarly, it’s important to note that the very modern or contemporary ideas of nation states didn’t really exist, right? You had things that were kind of building up to that in the time period that we’re playing around in, but it wasn't an entrenched kind of idea, like, “I'm American,” or, “I'm French,” or, “I'm this, that, or the other.” It was usually like, “I am from Paris. Anybody not from Paris? That’s a foreigner. I don’t really know ‘em.” There wasn't the same entrenched hatred that we experience with the rise of the concept of the nation.

Wythe Marschall: You might pay taxes to five different kings depending on where you live. You weren’t “of a nation,” you were just a hapless guy who had to pay taxes to different kinds of powers, and you had different ideas about them, c’est la vie. Modern nations didn’t exist. Everyone was interpreting things in a much more religious way than the reader possibly will be, unless we blow up with, like… I don’t know, whatever, some really specific communities. We’re just trying to be nice to everyone but focus on the fun things about a zombie apocalypse.

Will Savino: We’ve talked a lot about the setting and the framing here, but I’d be remiss if we didn’t at least quickly touch on the Grit System, which is the fundamental mechanical underpinning that makes this system run. And, oh god, I love the Grit System. I played in a very long Stillfleet campaign with Wythe, and there are two things about the Grit System that I think are genius and should be included in just about every RPG. That’s “ability score as die size” and the ability to gamble by taking your mana-equivalent and adding that to any role.

Those two things, I think, are fundamentally smart game-design innovations that I imagine gel perfectly with the OSR vibes of Danse Macabre, but is there anything else purely mechanically that you’re excited about that you’ve incorporated into Danse Macabre?

Chris Pickett: Yeah, for sure. One thing is: hard agree. I think the Grit System is brilliant, and I think that Wythe spent a lot a lot of time and did an extremely incredible job creating something that’s really player-forward and intuitive, easy to pick up, easy to learn, and lets you get into the meat of the setting and RP and all of that.

But yeah, Danse Macabre treats the Grit System a little bit differently. There are fewer scores, so it hews a little bit closer to MÖRK BORG and stuff like that, where you have fewer scores more broadly applied.

It also differs quite a bit in that for all of our Grit System games, they all have these “Powered by the Apocalypse-adjacent” powers, where it’s like, you burn grit, the thing happens. It’s very narrative. With Danse Macabre, I scaled that back quite a bit, and it looks closer to what you might see in Knave or OSE, things like that. Powers are much more low to the ground. It’s usually more like: you gain advantage on something, you add +1/+2/+3 to a roll, things like that.

I think that mechanically the thing that I’m genuinely the most excited about is the d100 list of maleficia that I touched on a little bit earlier. It’s a lot. It's a lot of different mutations that are all very biological, not super magical.

Will Savino: But they only come into play if you die.

Chris Pickett: Yes.

Will Savino: So, GMs: kill your players if you want Danse Macabre to be fun.

Chris Pickett. Yes, that’s very much encouraged. Take risks, do crazy shit, be lethal. Or, alternatively, run away, because the combat can be pretty fast and pretty lethal.

The list of maleficia in the chapter in the book is “Liber Maleficiorum,” thank you, Dr. Erica Bridges.

Will Savino: Please type this out so I don’t have to guess the Latin spelling of this.

Wythe Marschall: It’s just “the Book of Mutations.”

Will Savino: [laughs] I know, I know. I’ll just go to Latin Google Translate, I guess.

Wythe Marschall: The actual play group that's been running Danse Macabre, RP Jesters, have had a really interesting experience. You can have zero-to-three [maleficia] to start with, and you’re a criminal. Many of the criminals have died at least once and come back with a mutation, so they have zero-to-three to start. Some people have zero, and then it’s interesting, because if you have one, you’re like, “I should just die and get more powers.” If you have zero, you want the clean score.

Will Savino: Yeah, interesting.

Wythe Marschall: That’s actually happening. One character is a middle-aged religious person on the AP who is terrified to die because they’ve never died, and everyone else has. And they’re very weird. One of them is like a human/slug monster kind of thing. This mendicant person is so terrified, they’re not sure. Their faith has been shaken, and they don’t know what it’ll feel like to die and then just come back. And everyone’s, like, “oh, you know, yeah, it’s terrifying but you’ll get over it.”

But it’s an interesting thing that gives players two different ways to play it, where you can do min-max, OSR, goofy. Like if you were playing anything else, like DCC or Cairn, and you’re fighting skeletons, whatever. But a different way to do Danse Macabre, maybe closer to what Chris pitched as almost like a one-on-one very philosophical game is more like, “What does it feel like to not exist and then come back, and then your body isn’t the same.” It’s kind of a metaphor for aging, it’s kind of something we all face, but it’s a game. Ultimately. It’s fun.

Will Savino: Is it a trans allegory? Feeling a bit like The Matrix there.

Chris Pickett: Yeah, you know, as a queer person who identifies as non-binary—I don’t identify as trans—but definitely, yeah, my obsession with body horror just comes from having a body and watching it change really radically over time. But also, feeling alienated in your own body and trying to wrestle with what that feels like.

I really wanted that to be part of the experience of embodying your character, having them die, having them come back. You’re still the same person, but you're also different at the same time. It’s very, very weird, just wrestling with what it means to be human in a rapidly non-humanized body in a lot of ways.

Will Savino: One of my favorite tweets is, “I'm having a really hard time with body image. It’s so distressing to look in the mirror and see the image of a body.”

Anything else you want me to shout out just at the end of this?

Wythe Marschall: We have streaming games every Sunday during the campaign. We also have a big live event in New York City with some of the cast of Fun City. You can listen to Danse Macabre or you can watch the streams. If you happen to be in or around New York on October 26th you can come out to Stone Circle Theater in Ridgewood, Queens and see three of our favorite AP folks ever play Danse Macabre. One night only, big game. It’s gonna be different for us because we’ve run so many games with random people, but to run games with actors before—hopefully—a crowd of at least a hundred or so, right? I mean, who knows, it’s a big church with a stained-glass Jesus holding a lamb behind them. So I really hope people do check it out.

Will Savino: The first time I’ve ever been bummed to live in Buffalo, New York. I can’t attend that. That sounds awesome, though.

Chris Pickett: Take the train! Bring the family!