Every NPC a Short Story

When designing NPCs for your tabletop campaigns, think of each as an unfinished short story.

What does it mean to “create an NPC”? If you’re planning a tabletop campaign or writing tabletop content designed to be consumed by others, you’ll have to decide what constitutes a sufficient overview of a character in your world. Is an NPC merely a physical description + job + relevance to plot? Or do you define an NPC based on the D&D system of personality traits, bonds, flaws, and ideals? Maybe you think more mechanically: is an NPC a combination of stat block, a factional alignment, and a default disposition toward the player characters?

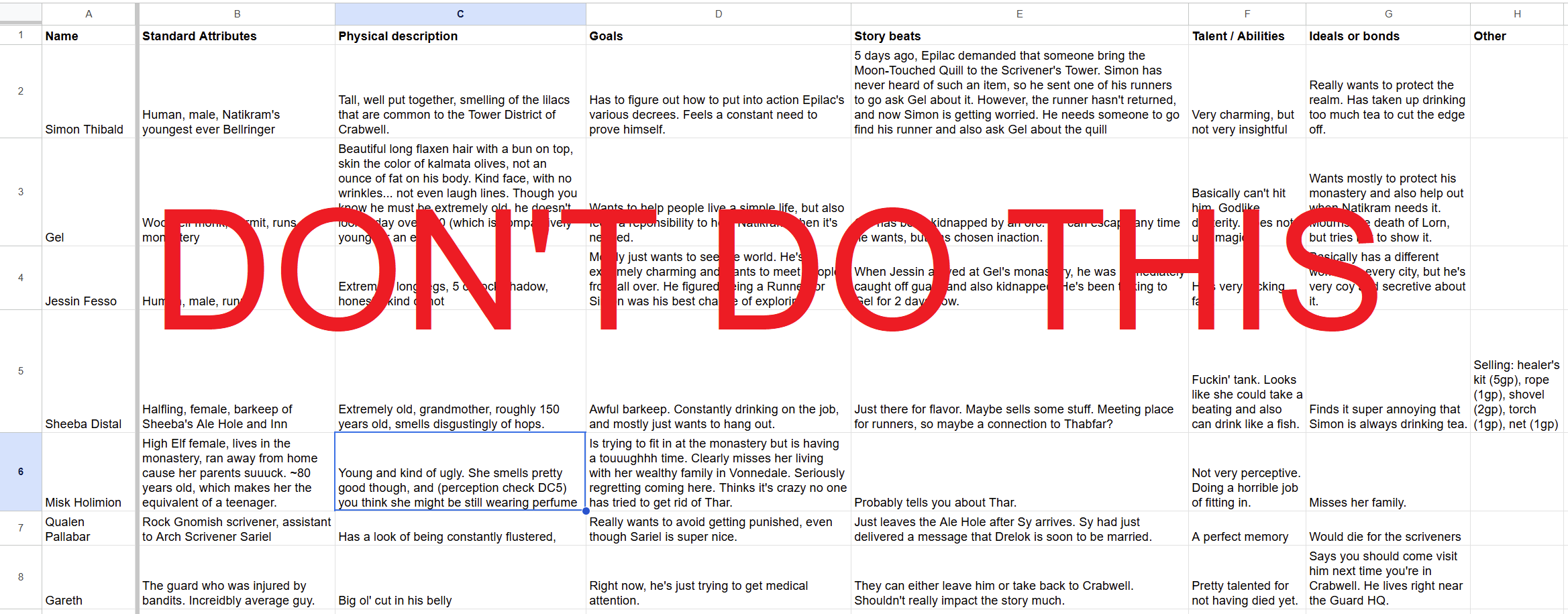

When I first started planning my own tabletop campaigns, the NPC descriptions in my notes were a bit of a mix of all of these. I used—and still use—Google Sheets to sketch out my sessions. Each sheet included a table of every important NPC with columns for standard attributes, physical description, goals, story beats, talents and abilities, ideals or bonds, and “other.” This was not a good system! It took way too long to fill in, and each column wasn’t relevant for each NPC. I thought that exhaustive planning and cataloging would help me to roleplay, but it became more of a chore to pore over these notes during session prep or while GMing.

These days, instead of thinking of my NPCs as a collection of data points, I tend to conceptualize each nontrivial NPC as an unfinished short story. This has helped me to essentialize NPCs, focusing both on what’s important and what’s interesting about each. This method tends to clarify their gameplay and narrative potential without railroading players into fixed courses of action. Let’s explore this method in a bit of detail.

What Is a “Short Story”?

When I say “short story,” I’m talking about concise prose fiction. It is narrative without fat. It is “about” a singular theme, idea, twist, mood, or moral. A short story need not be overly literary—that is: laden with symbolism, nuance, and layers of interpretation. However, it does need to have a point.

A short story omits superfluous details. When writing NPCs, you probably don’t want to predetermine their entire life story. What matters is only that one thing that’s most interesting about them right now.

In Kurt Vonnegut’s “8 Basics of Creative Writing,” he advises “use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted.” When you’re planning your own sessions, you are both the writer and the total stranger. As you actually run your session, you don’t want to have to comb through paragraphs of notes to remember the point of an NPC. Figure out what’s compelling about them—whether that’s some moral dilemma, an overwhelming need, or a twisted backstory—and prioritize that.

Now, I admit it’s rather confusing to think of NPCs as short stories when short stories normally contain characters. What I mean is that your idea for an NPC should suggest the outline of a short story. Find the plot in a character, the singular element that presents an interesting question or scenario for the players to consider.

Unfinished

Key to this NPC framework is that the short story is unfinished. The pieces are in place, the lean exposition is prepared, but the climax or resolution has yet to occur. This is absolutely essential, as it allows for the players to see the story through to its finish, thereby determining for themselves—and for the greater story of your campaign!—the final message of a character’s story.

- A priest doubts his faith. Does the party show him that belief and devotion are their own rewards? Or do they demonstrate that only skeptics control their destiny?

- A tavernkeep is possessed by a demon with a gift for hospitality. Does the party encourage the possessed tavernkeep, thereby ensuring the tavern remains profitable? Or do they exorcise the demon, dooming the town’s most successful business?

- A short-sighted ruler will soon die but has yet to choose a successor. Will the party force him to face his mortality and select a successor? Will they take matters into their own hands by hand-picking the next-in-line? Or will they let the people suffer as chaos reigns when the ruler dies?

Thinking of NPCs as unfinished short stories transforms NPCs from mere quest-givers into integrated story generation tools. A quest-giver hands the party a task; an unfinished short story tacitly invites the party for input. To be clear, there’s nothing wrong with an NPC giving out a quest, but that quest will certainly be richer if it ties into the shtick of the NPC. What is uniquely compelling about that NPC doling out that quest? Will that quest provide some resolution to the short story that defines them?

In this sense, crafting NPCs as short stories yields characters that are defined more by their narrative potential than their function as tools to be used by the players. An NPC is not simply an enemy, a vendor, a source of lore, or a quest-giver. They are pure narrative potential energy.

The Dearth of Lore

Short stories necessitate lean storytelling. This is a good framework to use for creating NPCs specifically because it forces you to prioritize what’s most important about a character. That does not mean, however, that your NPC can’t have fleshed-out backstories, layers of nuanced desires and fears, or a tangled web of social connections and factional affiliations. On the contrary, I think developing these details makes an NPC feel much more grounded, and it can inform quite a bit about how they interact with a party.

Nevertheless, I don’t think you should start your planning process by defining each of these details unless some particular aspect ties directly into the NPC’s short story. Focus on the short story first. Then, if the players ask about an NPC’s spouse, favorite food, or childhood home, you can either improvise, generate those details from a rollable table, or pull from extra notes you developed after planning the NPC’s central narrative hook.

Likewise, you can and should give your characters unique mannerisms, voices, and stats. When I’m running a 5e campaign, I always have a stat block at the ready for any halfway important NPC has the slightest potential to end up in a fight or casting magic or otherwise interacting mechanically with the party. The short story is the foundation; everything else helps to further flesh out the character.

On “What the NPC Wants”

Typical guidance for creating TTRPG characters suggests that you should always define an NPC’s desires first. This is necessary but not sufficient. A desire is not inherently interesting, and it does not necessarily drive the plot. If a king wants an army of orcs defeated, that’s acceptable as a motivation for the king, but it does not make the king compelling. In other words: a desire is only one aspect of crafting an NPC short story.

I’ve found that this is a common trap into which many new GMs fall. These GMs believe that desires define a person. In real life, maybe that’s true (!), but it’s not an automatic shortcut for compelling characters in fiction.

To reference Kurt Vonnegut’s writing advice again, “every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.” I love this advice! But when so much of RPG social dynamics are reduced to either fulfilling or defying the explicit wishes of NPCs, one additional degree of nuance and narrative flair can go a long way toward elevating the plot.

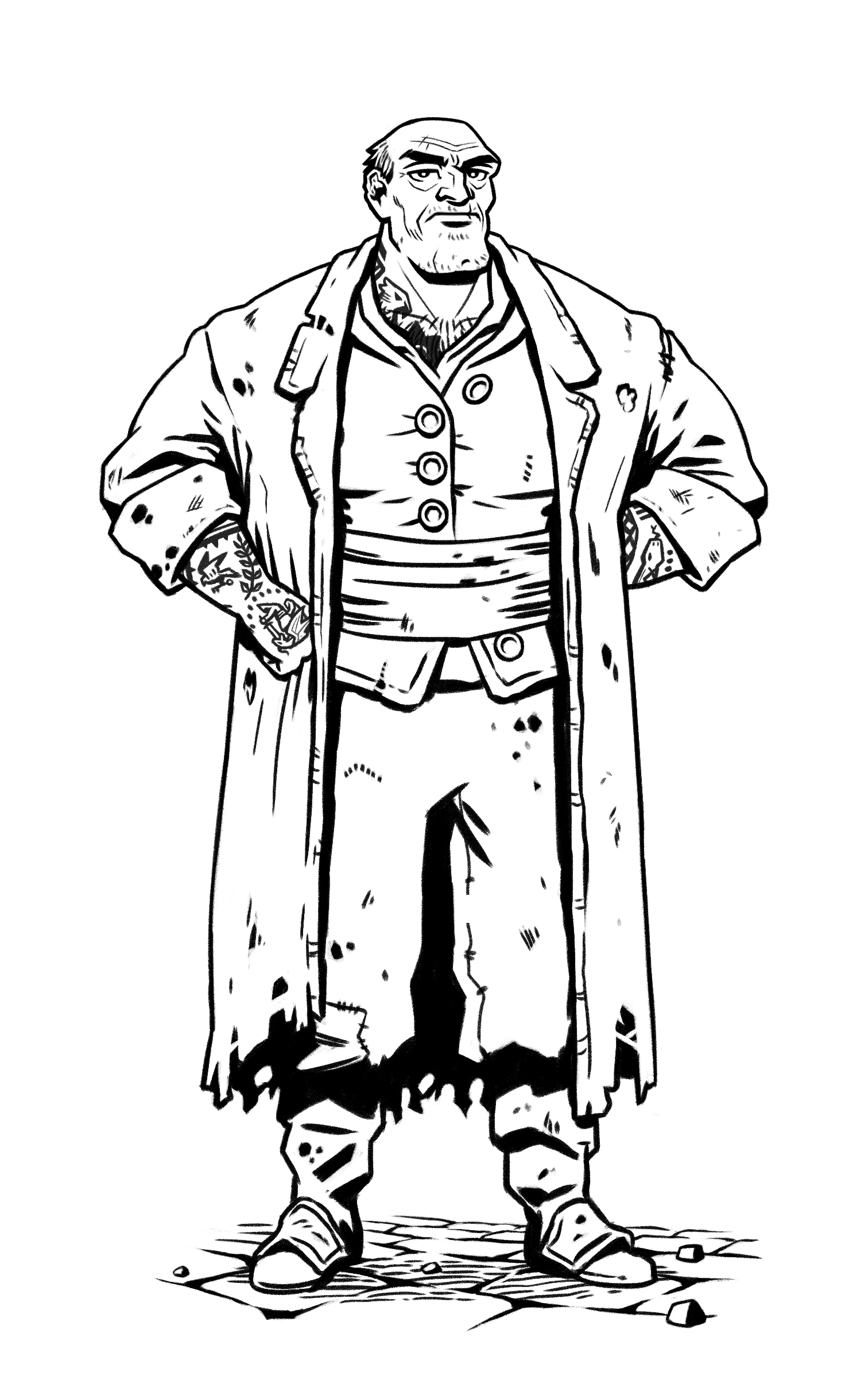

Example 1: Hamish the False Defector

Bandits have just set up a camp outside of town. Hamish claims to be a former member of the gang, but he is actually still on their payroll. He tells the party of adventures that he can help them to defeat the bandits. This is a lie. Hamish’s actual goal is to lead the party astray. However, he does truly have reservations about his life with the bandits. If the party is persuasive enough, perhaps they can convince him to defect in earnest. Otherwise, he’ll work against them.

Here’s a classic example of an NPC as a short story. Just by reading that paragraph, you can probably make many inferences about Hamish.

- He’s a good liar.

- He has some moral scruples or a bone to pick with his gang.

- He can work effectively on his own.

- He’s at least old enough to have ample history with a gang.

- Despite working with criminals, he is open to reason.

Hamish is not a quest-giver. The “quest” here is implicit. Bandits have arrived, and the party will likely want to deal with them. Hamish is there to add narrative texture and complicate the party’s efforts to topple the gang. How does Hamish feel about the other individual members of the band? What city is he from originally? Who or what does Hamish love? It doesn’t matter! Or, at least, it doesn’t matter right now. If the players decide to work with Hamish, you can always fill in those gaps as you go.

Example 2: Professor Ordumen the Ethical Necromancer

Professor Ordumen teaches necromancy and alternative agriculture at a magic school. She fancies herself an “ethical necromancer,” as she only raises the dead so that they can help perform labor in agricultural settings. Her magic is considered vile by many of the other professors at the school, but she posits that necromancy can be a tool used for good. She suggests that divine spellcasters ought to think more about the consequences of their faith and not merely the connotations.

Professor Ordumen is a very different sort of NPC from Hamish. There’s nothing in her short story that directly suggests a quest for the party to undertake. However, she is a professor at a magic school, and if you’re running a magic school campaign, there’s a good chance your party will meet her as result of their typical studies.

Does your party agree with Professor Ordumen’s use of “necromancy for good”? Does this inform how they interact with other NPCs who say that the ends justify the means? Does the party’s edgiest adventurer glom onto Professor Ordumen? How will the party act if the administrators attempt to have Professor Ordumen fired? These are all compelling questions that will enrich your narrative without relying on a one-size-fits-all quest structure.

Again, I’ve said almost nothing about Professor Ordumen’s background, personality, or quirks. As important as those details might sound, they’re all secondary to her primary narrative function.

Writing Your Short Story

The two examples I provide above are far longer than anything I’d put in my notes. I absolutely do not write paragraphs with proper grammar in my session plans. For Hamish, I’d probably write something like:

Hamish, middle-aged human man. Former member of the gang. Pretends to be a defector. Open to reason, but plans to betray party.

Maybe I’d make some note of where the party is likely to find him, which stat block he uses, what voice/accent I’ll employ, and some extraneous notes about his present circumstances. That said, I really do keep it as simple as the above snippet 90% of the time. Hell, I often have even shorter notes, relying instead on remembering what I had in mind or just winging it on the fly.

My point is that you don’t have to actually write anything long or detailed. You just need the idea for an NPC’s short story. How specifically you record that is up to you.

Of course, if you’re writing for others, you’ll have to be a bit more descriptive. When I’m writing NPCs for Borough Bound’s setting guides, I try to give GMs exactly what they need to roleplay the NPC. Usually, this means between 1 and 4 paragraphs plus maybe a handful of bullet points. Only the most complex characters—typically a central villain or ally to the party—gets more than that. I used to write quite a bit more for each NPC, but I found that doing so only muddied what was legitimately compelling.

Ultimately, the most interesting aspect of any character in any tabletop campaign will emerge as the result of interactions with the party. Tabletop RPGs are an interactive medium. You can write all the lore for a character that you want, but what your party will remember is how they interacted with the NPC and the impact that NPC had on the story. Thus, start designing every NPC by writing intriguing microfiction that will immediately hook your players.