Lore & Mortar #1: What Do They Eat?

Figuring out what your NPCs eat will help you answer auxiliary questions about how your setting works.

You're GMing a tabletop campaign. Let’s imagine a scenario in which you describe a small bazaar in a desert oasis. You want to follow that classic GMing advice of narrating what your players smell as a means to enhance immersion. You describe the odors of desert spices but also of freshly cooked meat. Real quick question: where did that meat come from?

“Oh,” you say, “I guess camels and whatnot come to drink at this oasis, and then hunters kill them?”

Yeah, that works.

“Or… actually, maybe since it’s a bazaar, merchants bring in the meat and trade it for whatever the bazaar is selling.”

That’s fine too!

“Does that make sense? Like, would the merchants have to cure the meat first? And then would you cook the cured meat or just eat it as is? What would the merchants eat along the way? In fact, maybe they'd bring the animals alive and then butcher them at the oasis? Or would that be too complicated?”

The answers to those questions aren’t necessarily important. The point is that you’re thinking about the questions. It’s easy enough for your players to measure their food rations in some mechanical sense, but it’s altogether a separate issue to explain where the hell the food comes from in any given setting. It is, however, the single most important piece of worldbuilding you must do whenever you’re creating a settlement. If mortal beings live somewhere—even in a fantastical land!—your worldbuilding better account for how they get their food. Luckily, as soon as you start asking questions about food, you're bound to find answers that will improve the rest of your worldbuilding in the process.

Shandification

Prehistoric YouTube video essayist MrBtongue released a now unavailable video titled The Shandification of Fallout1 back in 2013. In the video, he argued that Fallout: New Vegas had better worldbuilding than Fallout 3 in part because the designers of New Vegas put thought into how the various wasteland citizens would eat. At the time, I thought this was a perfectly reasonable critique, but as I’ve made a career out of designing fantasy settings, it’s become a foundational pillar of my worldbuilding.

When you describe where food comes from, your goal should not be to achieve perfect believability. Almost every tabletop setting crumbles under enough scrutiny. The purpose of clarifying where food comes from is that doing so immediately creates “intrigue opportunities.”2 For any peoples living prior to modern times, the acquisition of food was the single most important part of their lives. It was never guaranteed, and failure to acquire food and water meant death. Civilization arose when and where it did because it was a lot fucking easier to develop agriculture in the Fertile Crescent than anywhere else on earth. Food comes first and society second.

When you’re designing worlds for your tabletop campaigns, the easiest—but not necessarily best!—way to design coherent societies is to place them next to food sources: a port town filled with fisher folk, an agrarian community in a fertile valley, hunter-gatherers in a savanna teeming with wild game. But we’re talking about fantasy worldbuilding, so let’s try the opposite. Start imagining a location for a society that seems inhospitable, and then invent some fascinating means of subsistence.

This is a frequent method I employ when designing settings for Borough Bound. As discussed in our post about how we create our cities, the nugget of an idea always comes first, and then a brief comes second. The initial ideation phase is often a total free-for-all brainstorm, so there are no bad ideas. That often means we end up with setting ideas that don’t make sense from any practical standpoint. We then have to figure out how to square those logistical impossibilities.

Let’s go through a couple examples.

Case Study: Falthringor

My team and I really wanted to make a fortress setting. We decided to stick it on a blighted mountaintop. Great vibes. The initial idea was that it’s some ancient abandoned fortress now reinhabited by a people fleeing their former home. They were chased by giants all the way up into the hills and then snowy peaks where they find the castle Falthringor. They move in. Awesome!

But what do they eat?

Our Falthringor EP has some flavorful tunes to rock out to while you eat cured goat or mountain tubers.

Well, I could just throw my hands up at at that point and say, “it’s a blighted mountaintop, and they only have the food they brought with them. There’s no game or forageables, and they can’t farm. That’s that! They’ll just have to last as long as they can and then repeat the exodus.”

That could work. It legitimately makes for a cool story: a people on the run, a mighty fortress, dwindling food supplies. A sort of “self-inflicted” siege.

Alternatively, what could we do to make the setting more interesting and more internally consistent?

Well, first let’s consider the blighted mountaintop. The first thing I did was establish that the former inhabitants of the fortress were ancient alchemists. They poisoned themselves and the land surrounding their keep via endless experimentation. That answers two questions at once:

- What happened to the former inhabitants?

- Why is the mountain blighted?

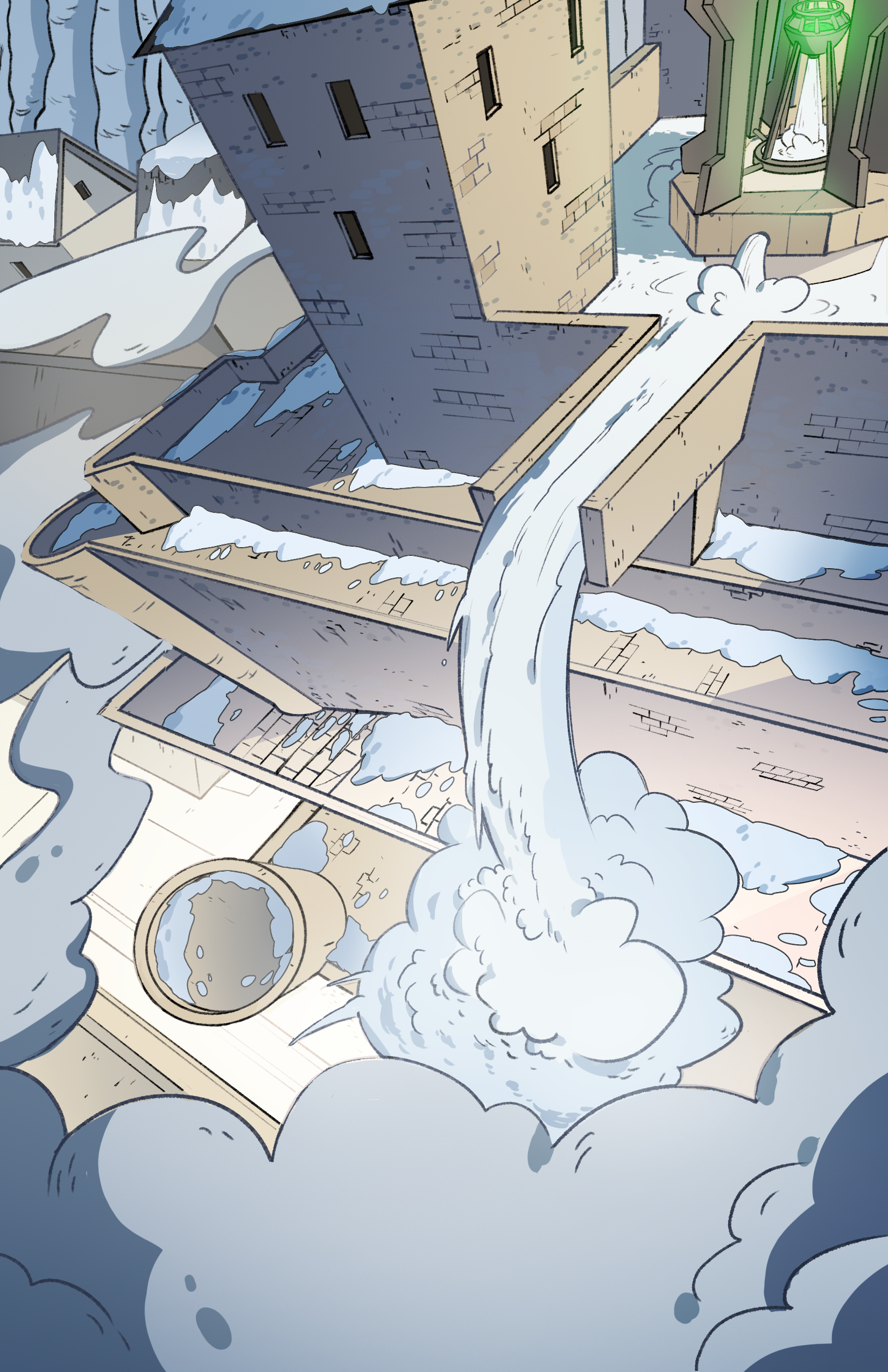

Now I’ve got a simple piece of lore that I can build upon. If alchemists used to live here, what sort of alchemical stuff is in the fortress? Most of alchemy is about transmuting one type of matter into another, so what if they had a means of creating fresh drinking water? That’s how we came up with the torrent opus, a device that perpetually deposits freshwater into a vast cistern under the fortress. In addition to being a cool bit of worldbuilding, it’s also a fabulous setpiece for our maps and illustrations.

Potable water isn’t enough, though. They still need food. Well, the blighting occurred a long time ago, and it likely would have been worst near the fortress. Maybe there’s arable land lower down in the foothills, but it really takes a lot of effort to farm. The magically pure water from the torrent opus might help with cultivation, but it’s still a challenge. And, of course, the giants are still a threat. The nobles all live within the fortress’s walls, but the farms need farming, and those farms are very difficult to defend.

This motivated the second bit of fun worldbuilding: the farms are just kinda far from the fortress itself. That means attacks from the giants are frequent and difficult to repel, and the armed forces are stretched thin. This requires the generals to make tricky decisions regarding how far they’re willing to go to protect the farmers, introduces a bit of a class conflict, and also provides an opportunity for quests as the players work to assist in the defense.

So what do the inhabitants of Falthringor eat? Pretty much just tubers and butchered meat and all that. It stores well (see: frigid peak), but it’s not an ideal scenario for anyone. If the players could assist the army, the farms would be better defended. If they could improve the torrent opus, maybe they could heal the cursed soil. If they think the nobles aren’t doing everything they can do protect the farmers, maybe the players could even help orchestrate a coup.

The Lesson of Falthringor

Ultimately, the answer to “what do they eat?” isn’t actually very interesting here. However, the question prompted me to add a bunch of satisfying narrative wrinkles to the setting that both further flesh it out and create opportunities for satisfying gameplay. In order for Falthringor to make sense, I had to consider how the citizens would feed themselves, and that line of questioning helped me to figure out the whole shtick of the setting. Considering food creates intrigue opportunities.

Case Study: Thestwick

The idea for our village of Thestwick-on-Alderham was that a humble community in the fen is turned upside down when a greedy duke tries to drain the fen to create farmland. Now, this immediately seems like the food must be more important to the story, right? The whole premise is about creating farmland! Believe it or not, food itself isn’t that important to any of the quests. Instead, considering how the villagers eat helped us to establish some unique traits for the NPCs and round out the surrounding world.

Given that “farmland creation” is the goal of the duke NPC, it follows that the fen should be broadly unfarmable to begin with. This tracks, as fens are usually not conducive to traditional agriculture. As we wanted to give the village a distinctly “shitty English countryside” feel, we decided eels would be an appropriately unique staple food for the villagers. The fen has creeks, and thus eel fishing seemed reasonable. But how do the villagers get the eels? One of our team members brought up the concept of cormorant fishing, a technique whereby fishermen train cormorants to catch fish for them. This was a perfect stylistic fit for the setting. We invented a cormorant-esque bird called the “moorwing” and made them a key feature of the setting. Moorwings prompted us to add an aviary to the setting and instantly spawned the unique NPC archetype of “moorwing eeler.”

The lack of farmland also made us consider what plants would grow out here in the fen. Not many trees, of course, as fens typically aren’t heavily wooded. The classic image of a dreary English fen calls to mind sedge and freshwater grasses and reeds. Of course, this also presents an opportunity to make something just slightly compelling. I invented the “thurleigh reed,” a rough fen grass that the eelers hate—as it obstructs their canoes—but which finds common use in rough fabrics and rooftop thatching. This is some of that mostly minor, incidental worldbuilding. It is not crucial or even terribly interesting. No player is going to become obsessed with the thurleigh reeds, and you are unlikely to weave them into your quests in any capacity. This solely helps with verisimilitude and to explain how the villagers are able to make many of their crafts, outfits, and homes with so few useful natural resources. It also adds a nice visual motif: the NPC outfits and all of the roofs have that rough and reedy look to them.

After our initial Thestwick release, we augmented the setting with a Holiday one-shot that features additional lore about the setting in winter. Quite honestly, I hadn’t considered how the change of seasons would affect eating habits until we tackled this follow-up. Once the creeks freeze, what would the villagers eat?

We reimagined the thurleigh reeds as producing sweet and spicy red berries only in the winter. Is that realistic? Who cares! It’s a simple explanation for an additional forageable, and the idea of a swamp grass producing charming red berries totally fits the Christmas-y aesthetic. We then imagined eelers drilling holes for ice fishing, migratory birds that only pass through during the winter, and brandy made from strange fen wildflowers. In the real world, these wintry food sources would seem too good to be true, but they’re entirely appropriate in a fantasy setting, especially for a holiday one-shot.

The Lesson of Thestwick

What does all of this add to Thestwick? It suggests a nuanced lifestyle for each of the NPCs. The villagers have a unique way of life that is challenging but charming. Catching river eels with water birds and harvesting berries from prickly grasses in winter is a hell of a lot more frustrating than just growing rows upon rows of potatoes, but that makes the duke’s scheme to drain the fen for farmland all the more compelling. Is the duke guilty of ecological tampering and the destruction of a unique culture? Yeah, probably. But also, farming would be easier than all of this. Again, the food itself isn’t important or necessarily compelling, but now that we’ve established this highly specific form of subsistence, players are forced to reckon with what the duke’s schemes would mean for these fenfolk or the land they inhabit.

List and Tables and So Forth

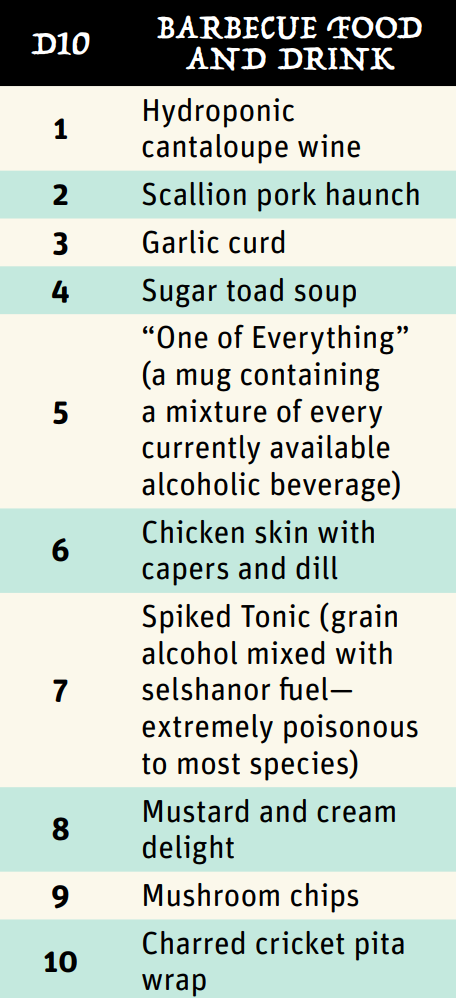

One impulse many GMs have is to design their worlds with endless lists of details. Maybe you figure out how a city sustains itself by writing d20 tables filled with crops, signatures dishes, and imported ingredients. This is absolutely an acceptable way forward, but I think it misses the forest for the trees. “Worldbuilding” doesn’t just mean heaps of lore and entries in a ledger. Good worldbuilding is about making your audience compelled and immersed.

The point of a list or table might be to rattle off food options when the players enter a tavern, but what does that really add? On the flipside, considering how a city grows, catches, imports, or concocts its food is likely to have knock-off effects that inspire the rest of your worldbuilding.

The key is that nothing should ever exist in a vacuum. If your port town feeds itself with fish, consider what they do with the fish bones. Consider who it is that actually does the fishing. Are they independent and just feeding themselves? Or do a handful of companies fish the whole bay and sell the fish at a premium? Consider the bay at different times of year. Is it harder to fish in the winter? If most food comes from the sea, do the townsfolk worship a watery god? Are there dangerous creatures in the water? What sort of infrastructure helps in the fishing process? Docks? Markets? Shipwrights? Canneries? What sorts of magic or technology do the fishermen and auxiliary workers employ?

You can and should make a list of unique fish and fish dishes that are important to this town, but the list is not the point. The point is what all of this says about the city, and what else it might imply about the wider setting. Food should always come first, but it should never be the purpose of your worldbuilding. The purpose is enriching the setting. Considering what people eat is your first step toward deeper worldbuilding.

So... What Do They Eat?

Food is crucial to tabletop worldbuilding, not because your players are likely to get super invested in individual dishes, but because you will inevitably make your world feel realer, more coherent, and more interesting by considering what everyone eats.

The food is not the point. The point is creating compelling settings, and starting with food acquisition often leads to intrigue opportunities that will bolster your setting's worldbuilding.

1 The meaning behind the term “Shandification” is a bit wonky. He compared the structure of New Vegas to that of The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, a novel by Laurence Sterne considered to be a noteworthy precursor to postmodern literature. MrBtongue’s basic point was that the meandering nature of an open world RPG means that seemingly incidental details carry more weight than they would in a linear story, and that devs ought to focus on those details to enhance the verisimilitude. He compares this with a "cinematic approach" that tends to be more linear.

2 Keep note of this phrase. “Intrigue opportunities” is a key goal of my worldbuilding, and I will reference it plenty throughout my Lore & Mortar articles.