The Hub-and-Spoke Dungeon

The hub-and-spoke dungeon is easy to design, easy to explore, and filled with unpredictable nonlinearity.

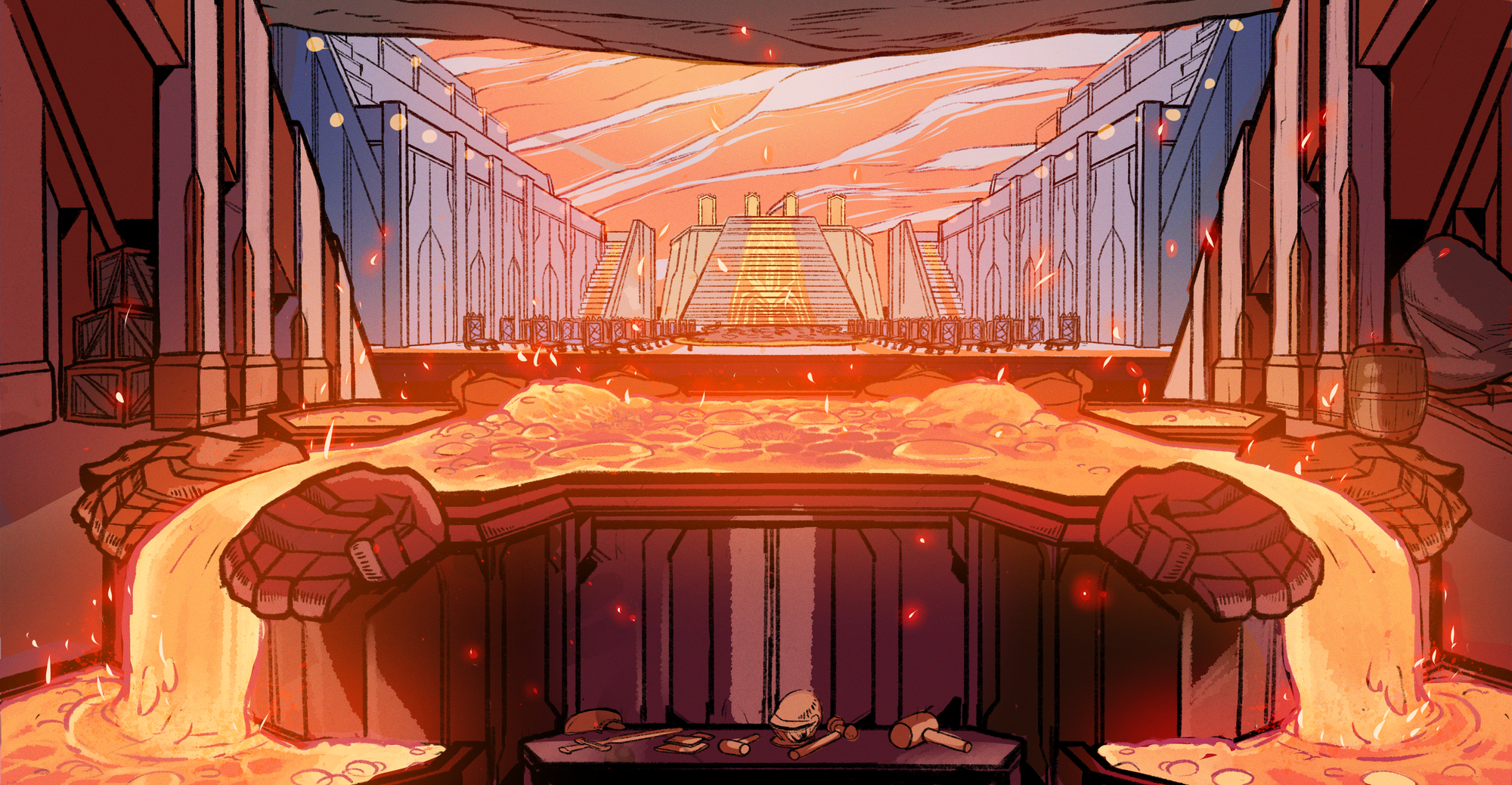

The adventurers enter a dilapidated factory on a barren, icy moon. A sprawling machine occupies the central chamber. The party slowly explores the factory, activating generators and unclogging great dynamos. As they complete tasks, the hulking machine in the center of the factory slowly reawakens. When, at last, the gizmo comes online, automated sentries attack the party. The adventurers strike at the automatons from moving walkways and rotating gears. They defeat the sentries and claim their prize: a fuel cell that will help them escape this frozen rock.

When you think of the “ideal” tabletop dungeon, you’re probably envisioning a sprawling, nonlinear complex with winding paths, secrets, and shortcuts. A map comes to mind, maybe something black-and-white with crosshatching. You pray that your players will explore every nook and cranny, get lost before reorienting themselves, and arrive at the boss/treasure room at the end with a sense of glee and dread.

That’s one type of dungeon. It’s a good type of dungeon, but it also has many drawbacks. In this blog, I’m going to talk about a different style of dungeon design that still emphasizes nonlinearity without ever placing excess mental load on the party with regard to navigation. This is the hub-and-spoke dungeon.

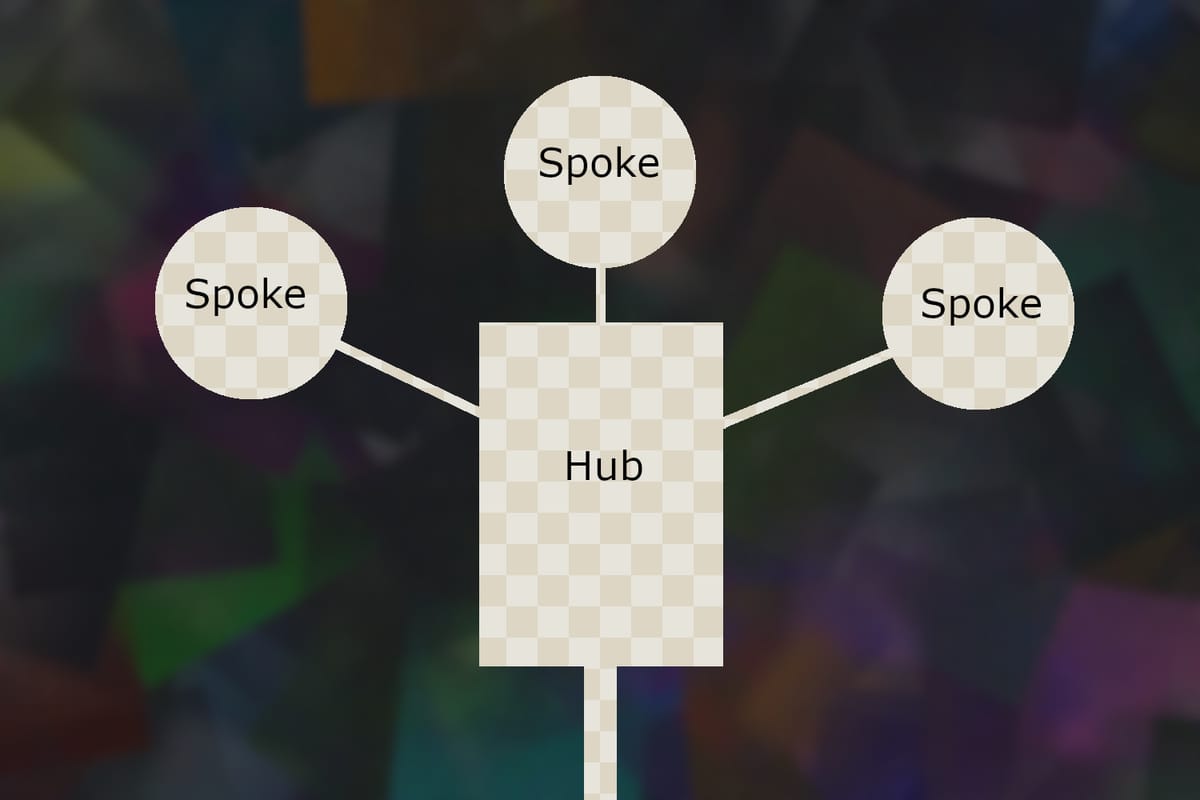

What Is a Hub-and-Spoke Dungeon?

A hub-and-spoke dungeon is shockingly simple in design. It has only three crucial elements, and it can be mapped out in seconds. Critically, a hub-and-spoke dungeon is extremely easy to run even without a map. It is ideal for campaigns that rely upon theater of the mind—note that this also makes it a perfect dungeon design for actual play podcasts or streams.

A hub-and-spoke dungeon has the following components, each of which I’ll describe in greater detail below.

- A noteworthy central chamber—the “hub”

- Three or more chambers branching from the hub housing distinct encounters—the “spokes”

- A final challenge

The hub-and-spoke dungeon format is compatible with plenty of other dungeon design guides (for example, the 5 room dungeon or my own social dungeon). The primary purposes of employing a hub-and-spoke design are to streamline the creation process, help your players visualize the space, and bake nonlinearity and player choice directly into the dungeon design. Let’s explore the elements of a hub-and-spoke dungeon before getting into why I think they’re so great.

Throw on this playlist whenever you're running dank dungeoneering sessions.

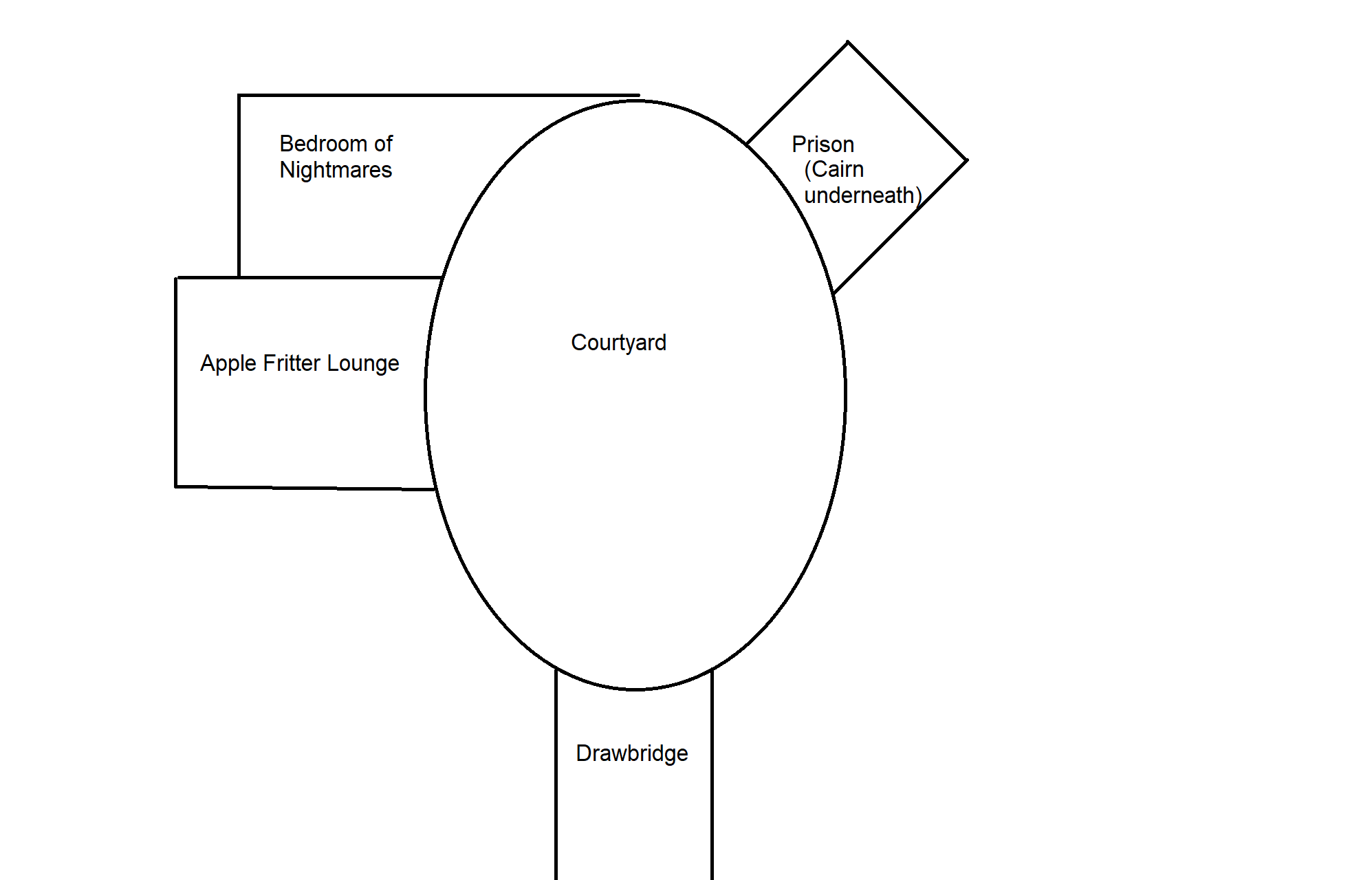

The Hub

The central chamber of a hub-and-spoke dungeon presents the players with the dungeon’s theme. It might be a grand ballroom, an enchanted hollow, or an open shaft at the center of a pyramid. Your players might have to face some sort of entry challenge—a locked front door, an initial miniboss monster, or some such—or they might just waltz right in. What’s crucial is that the hub itself is interesting. Perhaps there’s a fight immediately as they enter, maybe there’s loot hidden if they poke at the hub’s secrets, or maybe the hub presents a dungeon-wide puzzle—optional or otherwise—for the party to untangle. As the players repeatedly return to the hub, they continue to find something to do should they choose.

The hub tells your players what sort of dungeon this is. Obviously, there’s the aesthetic and tonal theming—is this a creepy mansion? an oppressive factory? a dank cave system?—but the hub should also present the players with some sort of goal. Here are some examples of goals that the hub might present.

- The door to a treasure vault won’t unlock unless the party completes challenges in the adjoining chambers.

- A critical NPC will not speak with the party until they earn the favor of sycophants in the adjoining chambers.

- A dragon is in stasis and will only wake if the party finds some MacGuffinitem in one of the adjoining chambers.

- A complex machine will activate once the party is able to manipulate mechanisms in the adjoining chambers.

- A collection of fairies must all assemble so as to teleport the party to some final location; the pixies are found in the adjoining chambers.

Did you notice what these ideas all have in common? They each require the players to explore and complete challenges in the adjoining chambers. That’s the key to a hub-and-spoke dungeon. It’s clear that the hub is the focus, but completing the dungeon requires thoughtful exploration, puzzle solving, and combat prowess in rooms that branch off from the hub.

In my favorite hub-and-spoke dungeons, the hub gradually evolves as the players complete challenges in the spokes. These can be subtle—a spiral staircase gradually winds its way up through the central chamber as the players complete challenges—but it’s better if they impact gameplay. Here are a handful of ideas for how to evolve the hub.

- Every time the players return to the hub, one or more new NPCs have arrived. These NPCs can help or hinder the party.

- Traps gradually reactivate as the party completes tasks in the spokes. Each return to the hub presents new obstacles to evade or deactivate.

- Lingering spirits gradually unravel the story of the dungeon one piece at a time.

- A sexy dinner party progresses from cocktails, to dinner, dancing, and then awkward coupling off.

- An ongoing battle evolves based on the party’s actions; either allied reinforcements arrive, or the enemy grows in strength.

An evolving hub need not mean gradually increased challenge, but it should equate to increasing complexity, either narrative complexity, roleplaying complexity, or mechanical complexity.

The Spokes

Multiple adjoining rooms/chambers/hallways/clearings branch off from the hub. These spokes should each become accessible simultaneously. That is, spokes should not gradually unlock as the players continue to explore. You can absolutely include additional locked chambers that the players can optionally open, but the primary spokes must be accessible in any order if you want the true hub-and-spoke experience.

Each spoke contains a unique encounter. When I say “encounter,” I don’t necessarily mean “challenge.” A spoke might contain a battle, a puzzle, a merchant, a diplomatic challenge, a chest with optional loot, a chest with critical loot, a complex device or machine that must be carefully manipulated, a moral dilemma, a red herring, or anything else. The spoke simply must contain something, and that something should motivate compelling gameplay.

The best spokes are multifunctional. If a spoke contains a combat encounter, consider giving the enemies lore tidbits to drop mid-fight. If the spoke contains a puzzle, consider presenting a hint for a different spoke that your players can only perceive via a difficult check. Maybe a social encounter in one spoke can lead to a helpful NPC assisting the party in the final challenge. Just because the spokes can be tackled in any order does not mean they must be entirely self-contained.

Here are a few additional considerations for spokes.

Make the entries to the spokes easy to conceptualize and catalog. Number the doors from left to right. Give each door a different color. Put the doors on different numbered floors of the hub. The key is that your players should be able to easily keep track of which spokes they’ve already entered and easily coordinate information they’ve gathered about each spoke (e.g. “we’ve been in the blue room and green room but not the red room” or “the clues were found on floors 2, 3, and 5”). Ease of navigation is absolutely critical.

Spokes can be optional. A spoke might just contain a generous healer, or it might contain a combat encounter solely intended to whittle down the party’s health. Maybe there’s only one spoke required to complete before finishing the dungeon, but the party doesn’t know which one. So long as the order the party chooses the spokes is up to them—and so long as you’re fine with the dungeon having an indeterminate length—you can make as many of the spokes optional as you wish.

Spokes can contain more than one room. First of all, spokes need not be “rooms” at all. They could be chambers of a cave, tents in a war camp, or glades in a forest. A spoke is just a discrete “zone” that branches off from the hub. Furthermore, a spoke might consist of two or more rooms, either branching out further or arrayed linearly. Just remember: the spokes should not connect to one another, and the simpler you keep the navigation, the better. Just because you can make each spoke a labyrinth unto itself doesn’t mean you should.

There should not be one “correct” order to visit the spokes. It’s okay if the party needs to return to a spoke later after collecting some key item in a different spoke, but if there’s only a single viable pathway through the dungeon, you’ve simply made a linear dungeon with extra steps.

The Final Challenge

As the players progress through the dungeon, exploring spokes and evolving the hub, they will eventually complete the necessary goal that the hub presents: they unlock some door, awaken some creature, or activate some mechanism. Upon completing this task, the party is faced with one final challenge. This part of the dungeon is absolutely bog standard! Just throw a final boss, escape sequence, or dangerous puzzle at the party.

The reason I add this point at all is because the final challenge should only be revealed once the party has completed the necessary steps you’ve established in the hub and various spokes. If there is a big powerful boss monster, there should absolutely be no way for the party to engage that monster until the rest of the mandatory portion of the dungeon is complete. The final challenge should be past the final door, or emerge only after awakening. The final challenge represents the culmination of the dungeon, and the point at which your players can probably stop thinking about the dungeon’s global geometry whatsoever.

Why Hub-and-Spoke Dungeons Work

Ease of Play

I can draw a hub-and-spoke dungeon on a piece of paper in about 30 seconds, and it will communicate everything that the party needs to know about where the various chambers are. This does not cheapen the dungeon because it’s not that kind of dungeon. This is not a labyrinth! This is a set of discrete encounters that interact with a central chamber.

To those of you who only ever play RPGs on Roll20 or Foundry with beautiful battlemaps and all that, this might seem completely unnecessary. Believe it or not, plenty of people run tabletop campaigns with only the simplest of visual aids, and sometimes nothing visual whatsoever. Whenever I’m playing in one of my online campaigns, it’s pretty much just a Discord call where I’ll very occasionally share my screen. Running complex mega-dungeons in a campaign like that is simply not feasible.

With a hub-and-spoke dungeon, though, it’s very easy for your players to say “wait, okay, there’s a room to the left, a room straight ahead, and a room in the middle… and remind me what’s in this big central room?” Boom, you’ve established the entirety of the geometry of your dungeon in a way that’s easy to digest and trivially easy to remember. This is doubly true for GMs running campaigns meant for additional listeners. I find that most actual play podcasts I enjoy focus on either minimal dungeoneering or only the most linear of narrative-focused dungeons crawls. A hub-and-spoke dungeon can work perfectly in podcast form, as the listeners can keep track of the party’s location without getting totally confused.

Ease of Design

You can create a hub-and-spoke dungeon in minutes. Seriously. Pick a visual theme for the central chamber, make up a few random encounters for each spoke, and then figure out what the players will face once the dungeon is complete. Obviously, it’s best if you can come up with a good narrative plus a compelling central “hook” to the dungeon and then carefully plan how the spokes will interact with one another and the hub, but that’s all bonus. It’s totally viable to say “there’s a big elevator in the central chamber that won’t turn on until you complete 3 challenges.” Boom, you’re 90% of the way there. Come up with 3 challenges and figure out what’s at the top of the elevator, and you’re done.

Nonlinearity

The best dungeons present story as they are explored. Perhaps the party comes across journal entries, or some diegetic worldbuilding reveals what happened to the dungeon’s former inhabitants. Hell, maybe the dungeon is filled with NPCs who just explain various details about this place or the current scenario. A hub-and-spoke dungeon can also present story, but because the spokes can be visited in any order, that story will necessarily be disjointed. That can be a nightmare if you want/need your party to follow a linear narrative, but if you plan a dungeon with a nonlinear story from the start, you can pepper neat little details into each spoke that the players must assemble into a cohesive narrative themselves.

Likewise, the nonlinearity of the hub-and-spoke dungeon can lead to great emergent gameplay. In a recent campaign, my players went to a spoke that contained potentially friendly NPCs right off the bat. The party successfully wooed the NPCs, meaning they had plenty of help for some fights soon after. However, most of the NPCs perished in these early fights, and thus the party had no help for the final boss. If, instead, the party had found the NPCs last, they may have struggled early on but found their forces greatly bolstered once it was time for the boss battle. Or, rather, they could have made enemies that screwed them over just before the final fight!

Finally, the nonlinearity of a hub-and-spoke dungeon is easy nonlinearity. Labyrinths are also nonlinear, but if the players decide to backtrack and explore other paths, it can quickly become a real headache. If the players get stumped in a puzzle chamber in a hub-and-spoke dungeon, they can quickly back out and reassess without getting lost or losing track of what the hell they were doing.