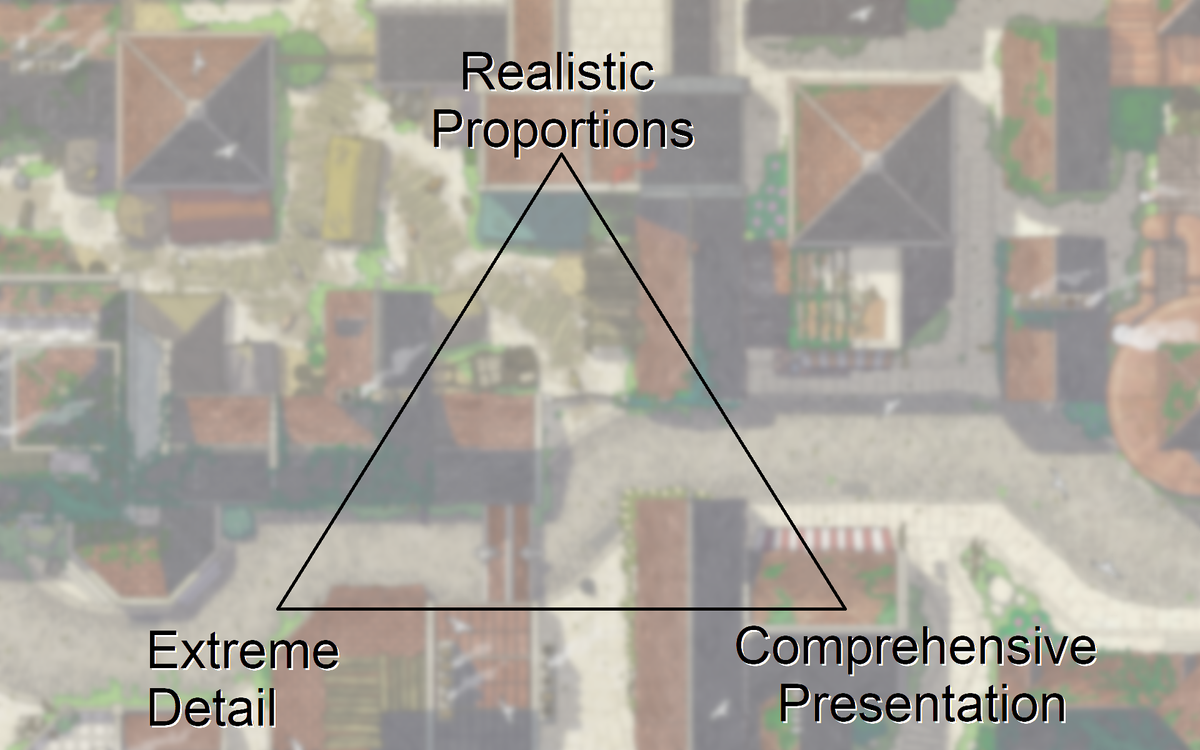

The RPG City Trilemma

Creators of fantasy cities always make sacrifices. It's important to understand the tradeoffs when creating massive tabletop settlements.

I design tabletop cities for a living. It’s the main thing we provide at Borough Bound: fully realized settlements that you can plop into your campaigns. These villages, town, and metropolises are meant to be big, compelling, detailed, complex, and—of course—they should provide plenty of opportunities for fun gameplay. I believe that we succeed at this, and I’d have to guess that our 1,000+ patrons agree.

However, when designing our city maps, we must alway make one of three potential compromise to achieve the fantasy of “fully realized” RPG cities. That’s not an admission of failure. Rather, every city you’ve ever explored in a tabletop RPG or video game was created by developers confronting these same three potential compromises.

The dream of a massive, comprehensive, fully-detailed city is simply not feasible to depict visually, and every team has to cut corners. I believe which corners are cut can have huge gameplay connotations, so it’s crucial that teams make the right choice. In this post, I’ll describe the balancing act that I’ve dubbed the RPG City Trilemma.

For now, I’ll mostly be discussing how this applies to tabletop city maps, but RPG creators face a similar quandary when writing descriptions of cities, designing quests in urban settlements, or creating additional RPG resources. Perhaps that’s something I’ll explore in the future!

The Trilemma

It is impossible to depict a large fantasy city with all three of the following attributes:

- Realistic proportions

- Extreme detail and interactivity

- Comprehensive presentation

Let me explain what I mean by each of these terms.

A city with realistic proportions is exactly as large as it says it is. That is: if the people in a city call it a metropolis, it actually appears as such. There are houses to accommodate tens or hundreds of thousands of citizens, hundreds of city streets, infrastructure to support all of these citizens, and an appropriately vast geographic footprint. Note that I’m talking about fantasy cities here, so even the largest “metropolis” likely won’t measure its population in the millions.

A city depicted with extreme detail and interactivity is given the highest level of attention on a minute scale. How you define “extreme detail” ultimately depends on the manner of presentation (the resolution of a topdown battlemap? the uniqueness of NPCs on digital streets? the mechanical reactivity afforded by a game engine or a tabletop guide?) but it is usually obvious when certain aspects of a city—or the very means of depicting it—feel rather impressionistic rather maximally meticulous.

A city that demonstrates comprehensive presentation shows you the entire city. A city block is not meant to act as a microcosm of the whole city. You can literally see every street, and you can trace the city from one edge to another. Obviously, not all cities are cleanly bounded; that is, many settlements gradually give way to farmland and then wilderness, thus it becomes hard to know what counts as truly comprehensive. That said, city depictions that forego comprehensive presentation usually do so in a rather extreme manner.

In order to create an RPG city for use in a tabletop campaign, you will always have to make sacrifices, and typically teams choose to reject one of these three attributes. Let’s take a look at some examples from video games to understand how these compromises reflect the difficult decisions city designers must make when designing tabletop cities.

Sacrificing Realistic Proportions

Video Game Example: Solitude from Skyrim

I initially referred to the RPG Trilemma as “the Whiterun Conundrum,” because it was the cities of The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim that helped to crystalize my thoughts on the topic. The developers of Skyrim sacrificed realistic proportions to make all of their cities. The city of Solitude is the prime example.

Solitude is meant to be the capital of the province of Skyrim, and yet it has only seven houses, five shops, an inn, two castles, a temple, and a bards college. Within the walls of the city, Solitude consists of two blocks plus a couple courtyards. In addition to an indeterminate number of generic guards and soldiers, there are slightly more than 60 NPCs.

Thinking about any single city in Skyrim makes each seem nonsensical. Solitude is, ostensibly, the greatest city in the region, and yet there are seven houses! However, Solitude does not feel as small as it sounds it should because the developers nailed the landing when it comes to details and comprehensive presentation. Every single building is fully furnished with thoughtful item placement and architecture. Every NPC has a (relatively) distinct personality, dialogue tree, appearance, and scheduled behavior. You can walk around the entirety of Solitude from the outside, and any building that you can see from a nearby mountaintop is also a building that you can enter.

Bethesda Game Studios place incredible value on a sense of simulationism in their games. They want you to be able to pick up any item you see, rotate it, and see it from every angle. They want every NPC—with few exceptions—to be one-of-a-kind. They want you to explore every interior and hop across any rooftop. It’s often janky, and they don’t always achieve perfect simulation, but broadly they achieve this singular goal better than almost any other game studio. That said, this was only possible in Skyrim because they populated its cities with far fewer buildings and NPCs than would be realistic. A shrunken scale became a necessity.

Tabletop Examples

Despite the drawbacks of shrinking the scale of a city, it is thus strategy that my team most often uses to build cities. There are a few reasons for this:

- As virtual tabletops become more popular, GMs and players desperately want to explore the entirety of the spaces they inhabit in full high-res detail. They want a consistent grid size, and they don’t want to have to suddenly switch to using theater-of-the-mind when some location is not mapped to the same scale as every other location.

- Mapping out an entire city at a high resolution allows for city-wide roleplaying and encounter design that makes no further compromises beyond the smaller scale. You can truly run a city-wide battle without having to rely on abstractions.

- No one else is doing it. As you’ll see below, there are dozens of TTRPG creators designing settings by making other compromises. Borough Bound is unique in this space by offering what we offer.

Take, for example, the city of Crabwell. According to its associated lore, Crabwell is the largest city in region, and yet it is proportioned like a Skyrim city. I think that most GMs are comfortable handwaving that fact because it means their players can explore and interact with the city in incredible detail, sneaking through crowded alleyways, riding rowboats down the canal, and exploring a half-dozen multi-floor interior maps for key locations. Yes, a realistically proportioned city would be far larger, but a city of this size and detail provides an incredible adventure sandbox for players.

Sacrificing Extreme Detail

Video Game Example: Novigrad from The Witcher 3

I can already see some of you disagreeing with me, but hold on for a second. Novigrad from the Witcher 3 is incredibly detailed, but the team had to cut a number of corners to make that work. Notably, the majority of buildings that you see are set-dressing. These buildings contain no plot-relevant content, and you cannot enter every door that you see. Likewise, most NPCs on the impressively bustling streets fall into one of a handful of NPC archetypes. That is: most people are not unique, and there is no way to interact with them other than shoving them aside or triggering their short barks. Outside of pursuing set quests, looting containers, and random combat with generic thugs, there are few ways to interact with the city itself.

As was the case with Skyrim, this sacrifice was completely justified based on the game design goals of CD Projekt Red. This isn’t a story about a flexible protagonist doing whatever they want as they explore the city, poking and prodding at every NPC and staging their own heists in random storefronts in different districts. Instead, the point of The Witcher 3 is for you to embody Geralt of Rivia and to pursue impeccably scripted quests. This is not a sandbox.

It is worth acknowledging the sheer scale of Novigrad, however. The city features hundreds of houses packed as densely as one might imagine they’d be in a free port city. Walking through the market and seeing dozens of on-screen NPCs at once—copy-and-pasted or otherwise—gives the feeling of a crowded city that doesn’t actually require meticulous scripting for each and every NPC’s unique schedule. What’s more, you can really see the entirety of Novigrad. I bet most players eventually hop in dinghy just to sail around Novigrad’s northern tip and admire the view of the massive city from every angle.

Tabletop Examples

This is by far the most common strategy used by tabletop RPG creators that want to highlight their cities without focusing too much on making them tactically usable. Typically, this means artists zoom out and render most buildings as either solid-color rectangles or abstract all structures into chunky city blocks. You often can’t see what material a building is made of, nor identify the nuances of the architecture, nor make out details like clutter on the streets. That level of detail simply isn’t a priority.

Instead, these maps sacrifice extreme detail so that GMs and players can make out the entirety of a city’s layout and get a sense for its true scale. Plus, players still have the option to point to a district or point-of-interest and say “I want to go there.”

If you’ve ever opened any D&D book, you’ve likely seen one of Mike Schley’s incredible maps at some point. My buddy Tom Cartos also has some stunning maps in his library, such as this dwarven city map by Marco Bernardini. You can’t exactly plop a token onto these maps; the point-of-view is simply too zoomed out. However, these maps are massive, evocative, and ideal for gameplay that focuses on theater-of-the-mind.

There’s a secondary advantage for zoomed-out maps such as these, and that’s the fact that you can always zoom in. Once you’ve designed the outline of a city in its entirety, you can create additional assets that highlight one particular district or neighborhood. That’s what we did with our city of Svarnahelm. Above, you’ll see a city map focused solely on geography, points of interest, districts, and thoroughfares. However, we are also producing focused releases that show off each district of the city. Our first such district was Wresyck Junction.

Other Examples I Enjoy

- Nassau Town by Limithron

- Duskvol from Blades in the Dark

- All of the town & city maps by Daniel’s Maps

- Jog Brogzin’s meticulous hand-drawn maps

Sacrificing Comprehensive Presentation

Video Game Example: Baldur’s Gate from Baldur’s Gate 3

In the eponymous city from Baldur’s Gate 3, players are able to speak to a truly insane number of unique NPCs, each with—at the very least—unique names and appearances. Players can interact with every element of the world in a richly tuned sandbox, casting spells, jumping across rooftops, and trudging through sewers like maniacs. They can rearrange stacks of explosive barrels to cause truly unreasonable explosions that spread through the streets. The level of simulation is high, at least on par with Skyrim. Plus, the city gives the impression of largeness, as streets are realistically crowded, and houses and businesses squeeze up against each other in dense tangles. So what’s the catch?

Well, you can only actually explore a handful of carefully curated districts within the city of Baldur’s Gate. You can see larger stretches of city in the distance, but the scale of the city shown on the title screen isn’t at all reflected in what you can explore in-game. Instead, the districts of Rivington, Wyrm’s Crossing, the Lower City, and—to a lesser extent—the Upper City act as suggestions of a much larger city.

Is this a downside? Not necessarily. Many players experience fatigue as they arrive at the final act of Baldur’s Gate 3, and so even if Larian Studios had infinite time and money, a theoretical fully-sized Baldur’s Gate would be a nightmare for pacing. There is merit in only giving players a handpicked selection of experiences. Why try to pepper the same amount of content over an impossibly vast play-space when you can instead dedicate all of your resources to fleshing out one smaller district with as much nuance and reactivity as possible?

Tabletop Examples

The classic tabletop example of a non-comprehensive city map would be a battlemap that shows only a snippet of an urban setting. Our friends at Czepeku are arguably the masters of this craft. When they are designing urban spaces, they make gorgeous battlemaps that show a tiny, hyper-detailed snippet of a city. These maps are perfectly designed for individual encounters: a fight, an investigation, a chase. The goal is not to provide a simulation of an entire city, but to focus on the most exciting, important, or visually distinct locales. Gamemasters can then either supplement this map with theater-of-the-mind roleplaying or additional maps to highlight different sections of the city.

Borough Bound also occasionally releases maps that forego comprehensive presentation. While our bread-and-butter remains cities that players can explore from corner to corner, a setting like Sootwyn Barrow has a different priority. Sootwyn Barrow is one of our more prescriptive settings; our goal was not to create a full simulation of a city, but instead a city setting that is home to one specific quest. This quest concerns a curse, a quartet of supernatural villains, and a roguelike structure that sees players repeatedly dying and attempting to complete the quest again-and-again.

Because the goal of Sootwyn Barrow’s map is to facilitate running Sootwyn Barrow’s quest, we didn’t feel a need to depict the entirety of the city. Instead, our map is a slice of the accursed village that suggests a larger city beyond but mostly focuses on the relevant play-space for the adventure. As Larian decided for Baldur’s Gate 3, we decided it was a better use of resources to populate a slice of the city with maximal gameplay density rather than trying in vain to make a massive, lesser detailed city map.

Other Examples I Enjoy

- Greek Square and similar maps from Borough Bound's interior cartographer Fantasy Atlas

- Shopping District by Crossland

- Black Market by Darkest Maps

- Town Center by by 2-Minute Tabletop

Resolving the Trilemma

Whenever you are designing a fantasy city, you’ll have to make a sacrifice. Which sacrifice you choose largely depends on your priorities.

Are you trying to show GMs the true scale of a city so that they can plan sprawling, theater-of-the-mind urban encounters? Then zoom out, minimize the fine detail, and show a big ol’ city map abstracting as much as necessary.

Do you want to give gamemasters a snippet of your city so that they can run individual encounters in high detail? Then zoom in, render the city in as much detail as possible, and narrow the frame to show only the necessary section of the city.

Do you want to let players explore an entire city in high detail, realistic scale be damned? Then do what we usually do: make moderately miniaturized but richly detailed cities and let GMs handwave the incongruous proportions.