What Tabletop GMs Can Learn From Elden Ring

Elden Ring can teach tabletop gamemasters useful lessons that will improve any TTRPG campaign.

Elden Ring is a design masterclass, and I’ve spent far too long pondering its many virtues and quirks. Despite the fact that it’s a (mostly) single-player, action-heavy video game, it presents many lessons that you can incorporate into cooperative, turn-based tabletop games. I’m going to decode some key insights that you—yes, YOU—can learn from Elden Ring, whether you’ve already become the Elden Lord or not.

Our DnD Boss Spotify playlist has a bunch of Elden Ring (and Elden Ring-inspired) boss battle music.

Narrativize Your Mechanics

Almost every one of the myriad mechanics that undergird Elden Ring’s RPG systems has a direct tie to the game's narrative and worldbuilding. You might read that and think, “sure, there’s lore for the swords and so forth,” but that’s just the surface level.

Take statuses, for example. The player and foes can inflict a handful of familiar status effects: sleep, poison, frostbite, blood loss, madness, scarlet rot (AKA ultra-poison), and death blight (AKA auto-KO). Without exception, there are heaps of lore about each of these effects. Sleep is tied to an entity known as St. Trina, who is an alter-ego of the empyrean Miquella. Scarlet rot is the domain of an outer god, and many characters are in the process of resisting or embracing it. Death blight is a comparatively new “force” in the world that only exists because of the inciting incident in the story’s plot. These status effects not just incidental mechanical details. They are intrinsically linked to what is happening in this world.

There are countless other examples throughout the game. Consumable items—food, flasks, rune arcs, and so forth—have plot relevance and aren’t just anonymous “healing potions”. Almost all spells have histories within the world (e.g. who created the spell? who are its practitioners? what are the philosophical implications of its usage?). Even the act of engaging with the game’s convoluted multiplayer systems is explained in-universe by grouping different types cooperators and invaders into different factions.

When I GM, I try to always connect the numbers on the players’ character sheets to the actual world the PCs inhabit. When your wizard learns a neat spell, consider who else in the world might know it, and what it might signify about the caster. A rogue has spectacular crits, but why? Your mechanics should answer questions about how the world works, and not simply dictate how your players roll dice.

Deploy Aesthetic Symbolism Liberally

Elden Ring’s lore is famously obtuse. The game doesn’t come out and tell you very much about its world without couching details in myth and riddle. However, astute players can glean a lot by taking stock of the game’s visual language. There’s a basic version of this where NPCs or factions use what amount to “logos.” It’s easy to tell if something is associated with Volcano Manor or the Carians based on their use of identifying emblems. There are, however, much more intriguing and subtle images that can prompt aesthetic reflection from players.

Spirals are a perfect example. The Shadows of the Erdtree expansion features ubiquitous spiral imagery: spiraling magic, a spiraled tower, and even two gargantuan trees spiraling around one another. What does this visual motif communicate? In-universe, spirals are often associated with the hornsent (a people), the Crucible (a sort of natural essence of the world), and divinity more broadly. In isolation, spirals mirror the common theme of alter egos and dual-identity across the major NPCs. And, perhaps most notably, a spiral resembles DNA.

So…what should the player learn by taking stock of all these spirals? I can’t say for certain! The spiral motif ties together themes of godhood, duality, and unfettered nature, but it’s not as simple as a factional emblem. It encourages the player to make mental connections between the primary themes of the game. A pretentious interpretation might say something about reaching upward to divinity through dialectical struggle, but even a simpler reading enriches your appreciation of the world, even if only subconsciously.

Alas, tabletop gaming is not as visual a medium as video games. That need not stop you from peppering such symbols throughout your game. You simply need to narrate your imagery. Let’s use the spiral example again. To employ spiral imagery in your campaign, describe architecture as spiraling. Describe trees as spiraling. Describe heraldry and artwork and fashion with words like coiled, twisted, or helixed. All of a sudden, your players start drawing connections. Maybe they think it’s all just clues to a puzzle, or maybe they accept that you’re adding a layer of poetic cohesion to your world. Even if they never treat your campaign like a piece of literature to be interpreted, the repetition alone builds meaning.

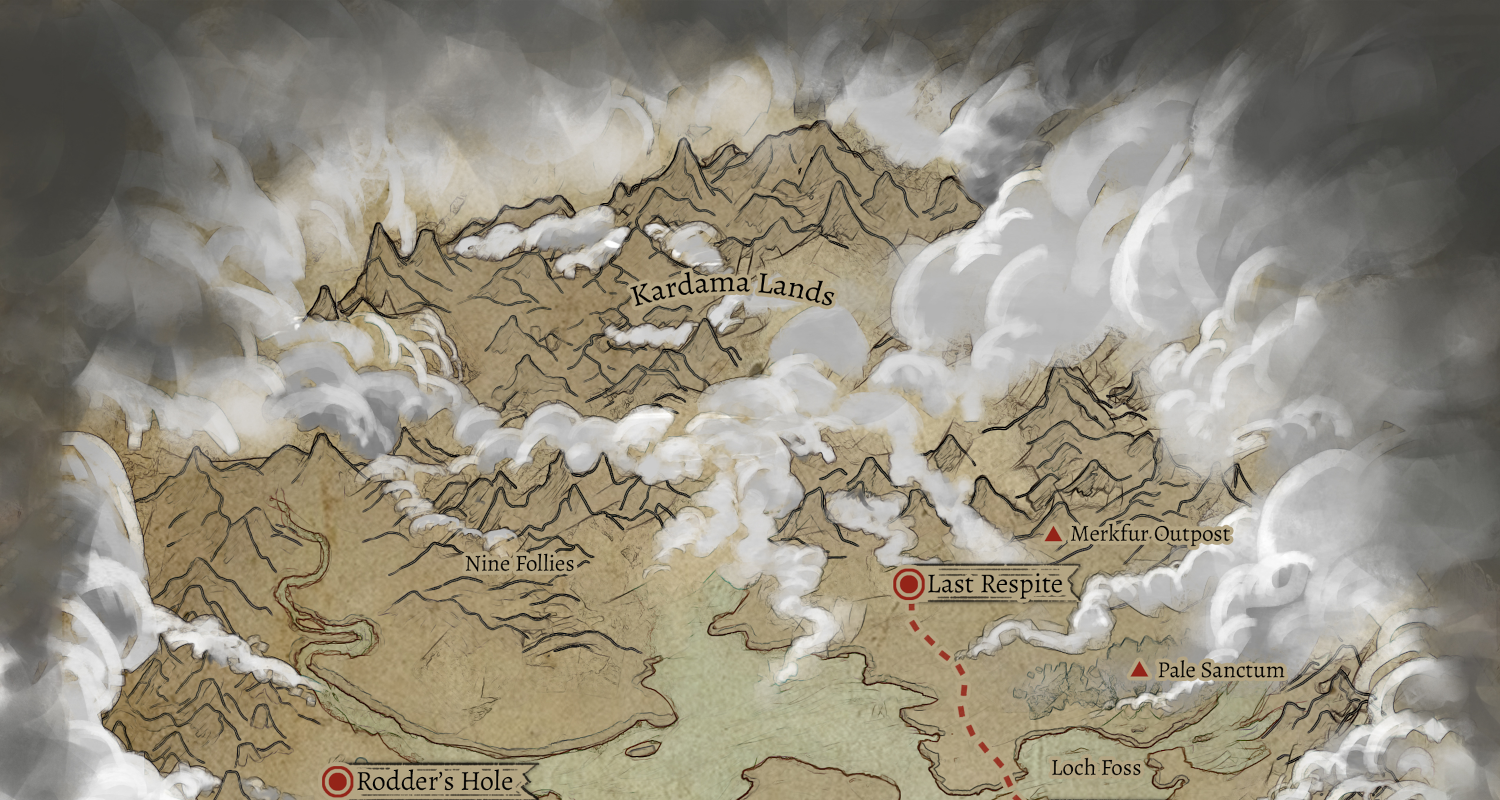

Undersell the Scale

A common experience when starting Elden Ring goes as follows. You enter the first area known as Limgrave. You open the map. It’s big! You eventually enter a teleporter and get yeeted way the hell away to another part of the world. You open your map. You are comically outside the bounds of what you thought was the entire extent of the world. Repeat this process multiple times, adding in an entire underground layer that is at least ⅓ the size of the surface. You are repeatedly floored as the full extent of the world reveals itself to be much larger than you had imagined.

This was one of my favorite little joys during my first playthrough, and it’s a technique I’ve employed in my tabletop games as well. I’ve argued in the past that you should keep your campaign worlds small—and I stand by that!—but that doesn’t mean you can’t expand the scope of your world as the players progress.

A common technique is to start a campaign in the terrestrial world and eventually branch into other realms of existence. If you’ve run a D&D campaign, I bet you’ve wowed your players by suddenly sending them to the Feywild, Shadowfell, the astral plane, the elemental planes, or one of the outer planes. Instantaneously, the scale of your play-space expands dramatically. This shows your players that there is more to explore, but also that the stakes of their adventure is likely greater than they had previously thought.

Even if you want to keep the literal scale of your world—that is, the geographic bounds in which they play—constrained, a good campaign will almost always up the epistemic scale. The more your PCs learn, the more they realize they don’t know. There are always greater secrets and scarier threats.

What Not To Do

A masterpiece is always imperfect, and Elden Ring is certainly a game with glaring flaws. Luckily, these failings are also instructive. Don’t make the same mistakes that Elden Ring does!

Don’t Obfuscate Key Motivations. Elden Ring is cryptic, and lots of stuff isn’t totally clear. That can be a slick way to handle worldbuilding in a fantasy game, but you really need to make sure your players at least know what the hell they’re doing and why. This is probably the great failing of Elden Ring’s narrative, and it’s entirely avoidable. Mystery is good, but you owe your players at least enough concrete facts to motivate their actions.

Dungeons Must Have Lore. Yes, I know that there is technically some nugget of unique lore to Elden Ring’s countless catacombs, tunnels, caves, and so forth, but they really spoiled much of the illusion of the game’s painstakingly crafted world. These visually indistinct dungeons often feel more like “content delivery vehicles” and not real spaces that have logical reasons for existing. If you absolutely must spam dungeons in your world, ensure there’s enough distinguishing lore for each.

Never Repeat Bosses. You can reincorporate trash mobs from one encounter to the next, but copying and pasting a boss wholesale is cheap and boring. A rematch is one thing, but a climactic encounter that is mechanically indistinct from a previous boss battle is an immediate letdown.

Scale Up Encounters to Account for Powerful Players. I’m straight-up not good at FromSoft games, but even I steamrolled most of the middle third of Elden Ring due to over-leveling. This robbed me of the satisfying challenge I was looking for. If your players have become quite powerful—either by using OP builds, clever party synergies, or wielding too many powerful items you’ve doled out—just friggin’ boost the threat level of your encounters. Ignore the recommendations of your game system. Find a way to challenge your players, because any combat-heavy game will be boring if the players never fear a foe.

Touch Grace

Your campaign is not going to be Elden Ring, and that’s good. You probably don’t want every NPC to speak cryptically, and you don’t want your players to die to every boss multiple times before succeeding. You don’t want combat to be the primary thing your players are doing for 99% of the game. Hell, I have a major bone to pick with all From Software worldbuilding, which is that their worlds never feel properly lived-in (e.g. where are the farms? where are the homes? who are you even fighting for if basically everything that lives is a monster?).

Nevertheless, it’s always helpful to steal great ideas from great works of art, and Elden Ring is an incredibly piece of interactive fantasy fiction. That alone should make it a worthwhile piece of study for any GM, novice or expert!